When you picture a penguin, what do you see? For many of us, it’s a tuxedo-clad bird waddling on a vast ice sheet, perhaps sliding on its belly into the frigid Antarctic waters. This classic image is iconic, but it only tells a fraction of the story. The world of penguins is far more diverse and surprising than most people realize. These flightless birds have conquered some of the harshest environments on Earth, from the blistering cold of the Antarctic interior to the scorching sun of the Galápagos Islands near the equator. Their evolutionary journey is a masterclass in adaptation, resilience, and specialized survival.

This comprehensive guide is your passport to meeting every single one of them. We will journey across the Southern Hemisphere to explore the unique characteristics, behaviors, and habitats of all the recognized types of penguins. We’ll delve into what makes each species special, from their distinctive calls and crests to their incredible breeding strategies and the conservation challenges they face. So, whether you’re a seasoned bird enthusiast or just someone who finds these charismatic birds utterly captivating, prepare to be amazed by the incredible variety within the penguin family.

Understanding the Penguin Family Tree

Before we meet each species individually, it’s helpful to understand what exactly makes a penguin a penguin. All penguins belong to the scientific order Sphenisciformes and the family Spheniscidae. They are a group of flightless birds that have, over millions of years, evolved to become supremely specialized for a life spent mostly in the ocean. Their wings have transformed into stiff, powerful flippers that propel them through the water with breathtaking speed and agility. Their dense, waterproof feathers trap a layer of air for both insulation and buoyancy, creating a characteristic silvery bubble trail as they swim.

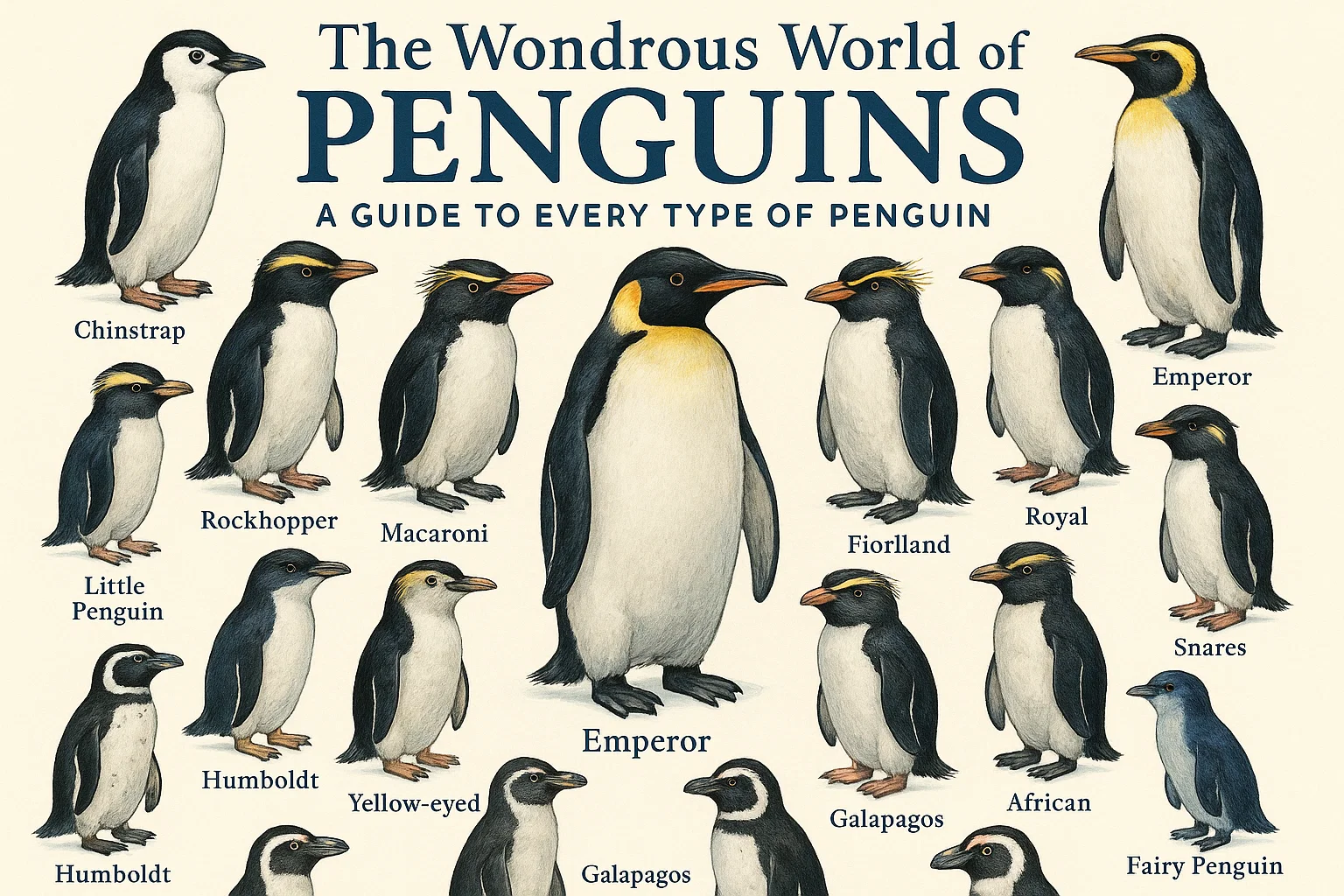

The number of recognized living penguin species can sometimes be a topic of debate among scientists, as DNA analysis continues to refine our understanding of their relationships. However, most major taxonomic authorities recognize between 17 and 19 species. This guide will cover the 18 most commonly accepted types of penguins, celebrating the rich diversity within this unique family. They are often grouped by genus and by the general region they inhabit, which helps us make sense of their distribution across the globe.

The Grand Emperors of the Ice

No discussion about the different types of penguins could start with any other species. The Emperor Penguin is the quintessential polar giant, embodying the extreme nature of Antarctic survival.

The Emperor Penguin

The Emperor Penguin is the undisputed monarch of the Antarctic. It is the largest of all penguins, standing nearly four feet tall and weighing up to 90 pounds. Their size is a crucial adaptation for surviving the brutal Antarctic winter, allowing them to conserve body heat. Their breeding cycle is legendary and unparalleled in the animal kingdom. As the Antarctic autumn deepens and other animals flee north, Emperor Penguins begin their long trek inland to their ancestral breeding colonies. Here, the female lays a single egg and immediately returns to the sea to feed, leaving the male to endure the harshest winter on Earth.

For over two months, the male Emperor Penguin balances the egg on his feet, covering it with a special brood pouch to keep it warm. He huddles together with thousands of other males in massive, rotating huddles where birds on the outside slowly move inward to escape the deadly wind chill. During this entire fast, he may lose nearly half his body weight. When the chick finally hatches, the male regurgitates a curd-like substance to feed it until the mother returns, bursting with food. It’s a story of incredible sacrifice and cooperation, a testament to the extreme lengths these types of penguins go to for their offspring.

The Regal King Penguin

Often mistaken for its larger cousin, the King Penguin is the second-largest penguin species and radiates a vibrant, majestic beauty. While they share the classic tuxedo coloration, King Penguins are distinguished by their striking orange ear patches that gradient into a splash of vibrant orange on their upper breast, unlike the Emperor’s more subdued yellow. They are sub-Antarctic birds, breeding on islands like South Georgia, the Crozet Islands, and Macquarie Island, where the climate, while cold, is less severe than the Antarctic continent.

King Penguins have a unique and prolonged breeding cycle. Unlike most birds, they don’t build nests. Instead, they also incubate their single egg on their feet. Their breeding cycle is so long—taking over a year from egg-laying to fledging—that they successfully raise only two chicks every three years. Colonies of King Penguins are often immense, containing hundreds of thousands of birds, creating a breathtaking spectacle of sound and movement. The chicks are covered in a thick, fluffy brown down, earning them the affectionate nickname “oakum boys” from early sailors, after the loose brown fiber used in ship caulking.

The Crested and Flashy Rockhoppers

Venturing into the sub-Antarctic realm, we encounter a group of penguins known for their punk-rock hairstyles and feisty personalities. These are the crested penguins, a genus characterized by vibrant yellow feather plumes that extend from their brows.

The Southern Rockhopper Penguin

The Southern Rockhopper Penguin is a small, dynamic bird overflowing with character. As their name suggests, they are famous for their method of moving across the rocky, uneven terrain of their island homes. Instead of a cautious waddle, they use their strong feet to leap from rock to rock, often with both feet together. Their most distinctive feature is the spiky yellow crest that starts from a yellow eyebrow and flares out behind each red eye, giving them a permanently surprised and rebellious look.

These types of penguins are tough survivors in a challenging environment. They breed on windswept islands north of the Antarctic Convergence, such as the Falkland Islands and islands off southern Chile and New Zealand. Their lives are dictated by the rough Southern Ocean, from which they extract a diet of krill, squid, and small fish. Unfortunately, Southern Rockhopper populations have declined significantly in parts of their range, likely due to climate change affecting ocean temperatures and food availability, making them a subject of serious conservation concern.

The Macaroni Penguin

With a name as flamboyant as its appearance, the Macaroni Penguin is one of the most numerous crested penguins. In the 18th century, “macaroni” was a term for a fashionable man who wore extravagant clothing, and these penguins, with their brilliant orange-yellow crests that meet in the middle of their foreheads, certainly fit the bill. They are very similar to the Royal Penguin, which some scientists consider a subspecies, but Macaronis are widespread across the sub-Antarctic.

Macaroni Penguins are dedicated ocean wanderers, spending most of their life at sea and coming to land only to molt and breed in massive, noisy colonies that can smell overwhelmingly of guano from miles away. They are superb divers, capable of reaching depths of over 300 feet in search of their preferred prey: krill. They are a vital part of the Southern Ocean ecosystem, and their immense population numbers make them a key indicator species for the health of the marine environment.

The Royal Penguin

The Royal Penguin presents a fascinating case of isolated evolution. For many years, it was considered a subspecies of the Macaroni Penguin due to its nearly identical body shape and crested plumage. However, it is now generally classified as a separate species, Eudyptes schlegeli, distinguished primarily by its face color. While the Macaroni has a black face, the Royal Penguin has a distinctive white or pale grey face.

This species has a remarkably restricted range, breeding almost exclusively on Australia’s Macquarie Island and nearby Bishop and Clerk Islets. This isolation is what allowed it to develop its unique facial coloration. Their biology and behavior are otherwise very similar to their Macaroni cousins, involving large, dense colonies and a diet heavily reliant on krill. Their limited breeding grounds make them particularly vulnerable to any localized threats, such as introduced predators or disease outbreaks.

The Erect-Crested Penguin

As the name implies, the Erect-Crested Penguin has yellow crest feathers that are particularly long and stiff, projecting directly upwards from above its eyes. This gives it a perpetually alert and sophisticated appearance. This is a poorly understood and threatened species, breeding on only two remote island groups: the Antipodes Islands and Bounty Islands of New Zealand.

Their remote habitat makes them difficult to study, but their population has been in a steep and worrying decline for decades. The reasons are not entirely clear but are likely linked to changes in oceanographic conditions that affect the supply of their marine prey. They are known for their bizarre and seemingly brutal breeding behavior: a female will often lay two eggs, but the first, smaller egg is almost always kicked away and ignored, with all parental care devoted to the second, larger egg. The evolutionary reason for this remains a mystery.

The Fiordland Penguin

Also known as the Tawaki, the Fiordland Penguin is a shy and elusive crested penguin native to the temperate rainforests of New Zealand’s South Island and Stewart Island. Unlike many penguins that prefer open beaches, Fiordlands seek out secluded coastlines, dense vegetation, and even caves for their nesting sites. They are characterized by a broad, yellow crest that starts from the base of their bill and sweeps back over the eye, ending in a drooping plume.

These types of penguins are solitary nesters or found in very small, scattered groups. They are mostly nocturnal on land, likely as an adaptation to avoid predators. During the breeding season, one parent will guard the nest while the other goes on long foraging trips that can last for weeks, traveling hundreds of kilometers to find food for their growing chick. Their secretive nature and remote habitat make population estimates difficult, but they are considered threatened due to introduced predators like stoats and dogs.

The Snares Penguin

The Snares Penguin is another New Zealand endemic, named for its exclusive breeding grounds on The Snares, a small, predator-free group of islands south of the country’s mainland. They are a medium-sized crested penguin with a vivid yellow band that starts at the base of their stout, red-orange bill and extends back over the eye into a drooping plume.

Because their breeding grounds are so protected and inaccessible, Snares Penguins have relatively stable populations. They are incredibly faithful to their colony, with breeding pairs often returning to the exact same nest site year after year. Their arrival at the breeding colonies is a synchronized event, with all the birds coming ashore within a remarkably short period. This “safety in numbers” approach likely helps overwhelm any potential predators in the water during the critical landing period.

The Banded Beauties of the South

This group includes some of the most widespread and familiar types of penguins. They are often characterized by a single black band across their chest and are highly adapted to a range of climates.

The Magellanic Penguin

Named after the explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who first spotted them in 1520, the Magellanic Penguin is a classic black-and-white “banded” penguin. They are easily identified by the two distinctive black bands between the head and the breast—one that runs in a horseshoe shape around the front of their neck and a second that curves down the sides of their body—and a generous amount of pink exposed skin at the base of their bill.

These penguins are inhabitants of the temperate coasts of South America, breeding in large burrows they dig in sandy soil or guano on the coasts of Argentina, Chile, and the Falkland Islands. This burrowing habit protects their eggs and chicks from the hot sun. They are tremendous migrants; after the breeding season, birds from Argentine colonies swim thousands of miles north, reaching as far as southern Brazil in search of food, demonstrating an incredible navigational ability.

The Tiburón Ballena: Unveiling the Mysteries of the Ocean’s Gentle Giant

The Humboldt Penguin

The Humboldt Penguin is a close relative of the Magellanic, African, and Galápagos penguins, all of which share the banded chest pattern. It is named after the chilly Humboldt Current that flows north along the western coast of South America, bringing the nutrient-rich waters that sustain its life. They have a mostly black head with a white border that runs from behind the eye, around the black ear-coverts, and joins at the throat. They also have a prominent, fleshy-pink base to their bill.

These types of penguins are highly adapted to a hot climate. They breed in burrows or on rocky shores under cliff overhangs to escape the desert sun of Peru and Chile. Like their relatives, they face significant conservation threats. Their populations have been severely impacted by overfishing of their prey species (primarily anchovies), entanglement in fishing nets, and historical guano mining, which destroyed their nesting burrows. They are currently classified as vulnerable to extinction.

The African Penguin

The African Penguin, also known as the Jackass Penguin for its loud, braying donkey-like call, is the only penguin that breeds on the African continent. Found on the southwestern coast of Africa, it thrives in a climate that seems utterly improbable for a penguin, dealing with intense sunshine and air temperatures that can soar.

To cope with the heat, African Penguins have several clever adaptations. They have a patch of bare pink skin above their eyes. When they get too hot, more blood is pumped to these areas, and the heat is released into the air, acting as a natural radiator. They also spend the hottest parts of the day swimming or hiding in burrows or under scrub vegetation. Despite these adaptations, their population is in catastrophic decline due to a catastrophic shortage of food linked to commercial fishing and shifts in prey populations, earning them an endangered status.

The Galápagos Penguin

Hold onto your hats, because the Galápagos Penguin is a true anomaly. It is the only penguin species to live north of the equator, making its home on the volcanic islands of the Galápagos archipelago. This is only possible because of the frigid, nutrient-rich waters brought by the Cromwell and Humboldt Currents, which allow these penguins to survive despite the equatorial sun.

They are the second-smallest penguin and are closely related to the Humboldt Penguin. Their existence is a delicate balancing act. During El Niño events, when ocean temperatures rise, their food supply disappears, and breeding ceases. Many penguins starve, and their population can plummet dramatically. With climate change predicted to increase the frequency of strong El Niño events, the future of these unique and tropical types of penguins is highly uncertain. They are the rarest penguin species and are endangered.

The Residents of Down Under

Australia and New Zealand are home to a unique set of penguins, from the smallest in the world to a species that shares its home with bustling cities.

The Little Penguin

The Little Penguin, also known as the Fairy Penguin, holds the title of the smallest of all penguin species. Standing just about 13 inches tall and weighing a mere 2 to 3 pounds, they are a compact and adorable package. They have a slate-blue plumage on their back and head, which earned them the alternative name “Little Blue Penguin” in New Zealand.

These diminutive birds are found along the southern coasts of Australia and throughout New Zealand’s coastline. They are nocturnal on land, a behavior that helps them avoid predators. At dusk, observers can witness the famous “penguin parade” at places like Phillip Island, Australia, where hundreds of Little Penguins waddle out of the surf and cross the beach to their dune burrows after a long day of fishing. They feed primarily on small fish and are agile swimmers, using their small size to their advantage in the water.

The Yellow-Eyed Penguin

The Yellow-Eyed Penguin of New Zealand is often considered one of the world’s rarest penguins. It is a solemn, majestic bird, easily identified by its pale yellow head and the striking band of bright yellow feathers that runs around its eyes and around the back of its head. Unlike the boisterous colonies of other species, Yellow-Eyed Penguins are fiercely private and prefer to nest out of sight of other pairs, often in the shelter of the native flax plants or forest on the South Island’s coast.

This solitary nesting habit makes them particularly sensitive to disturbance. Their population is critically threatened, with an estimated fewer than 4,000 individuals remaining. The primary causes are habitat destruction, introduced predators like stoats and ferrets, and diseases. Intensive conservation efforts are underway, including predator control, habitat rehabilitation, and a public hospital for sick and injured birds, but their future remains precarious.

The Unique and Isolated Species

Some penguins stand alone, either through their distinct evolutionary path or their highly specialized location.

The Chinstrap Penguin

The Chinstrap Penguin is unmistakable. It looks as though it is wearing a sleek black helmet with a very precise thin, black line running from ear to ear under its chin. This “chinstrap” gives it a cheeky, helmeted appearance. They are one of the most abundant penguins in the world, with breeding populations numbering in the millions, primarily in the Scotia Sea region on islands like South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.

Chinstraps are often described as bold and aggressive. They build circular nests from stones, and theft of these precious nesting materials is a common cause of noisy squabbles between neighbors. They are incredible mountaineers, often nesting on steep, rocky slopes high above the sea. Their “no-fuss” attitude and high-energy personality make them one of the most entertaining types of penguins to observe in their chaotic, bustling colonies.

The Gentoo Penguin

The Gentoo Penguin is the third-largest penguin species and a master of diversification. They are easily recognized by their bright orange-red bill, a wide white stripe that sweeps across the top of their head like a bonnet, and their most famous feature: a brilliantly white tail that they wag back and forth as they walk. They are the fastest underwater swimming penguins, capable of reaching bursts of speed up to 22 miles per hour.

Gentoos are highly adaptable and have a patchy distribution across the sub-Antarctic, with a significant population on the Antarctic Peninsula. They are opportunistic feeders and are generally the first to recolonize an area after a glacier has retreated. Unlike many polar species that are suffering from climate change, some Gentoo populations are actually expanding their range southward as warming temperatures make new areas accessible to them, demonstrating a remarkable resilience.

The Adelie Penguin

The Adelie Penguin is the classic, cartoonish Antarctic penguin. With a completely black head, white eye-ring, and a hint of a red bill, they have a simple but elegant appearance. They are one of only two true Antarctic penguins (along with the Emperor) and are a key indicator species for the health of the Antarctic ecosystem. Their name comes from the wife of French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville, Adèle.

Adélies are famous for their incredible migratory journeys, traveling thousands of miles between their winter feeding grounds and their rocky, ice-free summer breeding colonies. They are also notorious for their curiosity and their use of stones for nesting. A male Adelie will often present a choice stone to a female as a courtship gift. However, they are also notorious thieves, and a penguin turning its back on its nest for a second will likely find its best stones stolen by a neighbor.

The Conservation Status of Penguin Species

The playful waddle and comical antics of penguins often mask a grim reality: many types of penguins are in serious trouble. Of the 18 species discussed, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), more than half are threatened with extinction. Their status ranges from Vulnerable to Endangered and even Critically Endangered. The threats they face are complex, interconnected, and largely driven by human activity.

The primary dangers include climate change, which is warming oceans, melting sea ice (crucial for some species), and altering the distribution and abundance of their prey like krill and fish. Commercial overfishing directly competes with penguins for these same food resources. Pollution, from oil spills to plastic debris, kills penguins and degrades their habitat. Introduced predators, such as rats, cats, and stoats, ravage eggs and chicks on islands where penguins evolved without any land-based threats. Protecting these incredible birds requires a multi-faceted global effort involving marine protected areas, sustainable fishing practices, climate action, and on-the-ground conservation work to eradicate invasive species and manage diseases.

Conclusion

Our journey across the Southern Hemisphere to explore the different types of penguins reveals a group of birds that is far more diverse, adaptable, and fascinating than the common stereotype suggests. From the frozen deserts of Antarctica to the tropical waters of the Galápagos, penguins have evolved an incredible array of strategies to survive and thrive. Each species, from the towering Emperor to the tiny Little Blue, plays a unique role in its ecosystem. However, this incredible diversity is under threat. The story of penguins is now also a story of conservation, a urgent call to protect these charismatic birds and the delicate marine environments they depend on. By understanding and appreciating all the types of penguins, we take the first step toward ensuring their survival for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions About Penguins

How many types of penguins are there?

Most scientific authorities recognize 18 different living species of penguins. However, this number can sometimes be a topic of debate among biologists as genetic research continues to provide new insights into the relationships between different populations. So, when someone asks about the number of types of penguins, the most common and accepted answer is 18 unique species.

Where can you see different types of penguins in the wild?

You can see various types of penguins in the wild across the entire Southern Hemisphere. For Antarctic species like Emperors and Adélies, specialized expedition cruises to Antarctica are necessary. Sub-Antarctic species like Kings and Macaronis can be seen on trips to islands like South Georgia. You can see Magellanic Penguins in Patagonia (Argentina/Chile), African Penguins in South Africa, Little Penguins in southern Australia and New Zealand, and even Galápagos Penguins on a few specific islands in the Galápagos archipelago.

What is the biggest threat to penguins worldwide?

There is no single biggest threat, but rather a combination of severe pressures. Climate change is a massive overarching threat, as it alters sea ice ecosystems and ocean food webs. This is closely followed by overfishing, which directly reduces their food supply. Pollution (especially oil spills), introduced predators at their breeding sites, and human disturbance also pose significant dangers to different types of penguins around the world.

Do all penguins live in cold, snowy places?

Absolutely not! This is one of the biggest misconceptions about penguins. While many types of penguins are associated with Antarctica, several species live in very temperate or even warm climates. The Galápagos Penguin lives right on the equator, the African Penguin lives on sunny beaches in South Africa, and the Humboldt and Magellanic Penguins live along the coasts of Peru, Chile, and Argentina. These species have special adaptations, like bare skin patches for heat release, to cope with the warmer temperatures.

What can I do to help protect penguins?

There are several meaningful actions you can take. Supporting reputable conservation organizations that work directly on penguin research and protection is a great start. Making sustainable seafood choices to reduce pressure on fish stocks helps protect their food supply. Reducing your carbon footprint to combat climate change is crucial. If you visit penguins in the wild, always use a responsible tour operator that follows guidelines to minimize disturbance. Finally, spreading awareness about the challenges penguins face helps build broader support for their conservation.