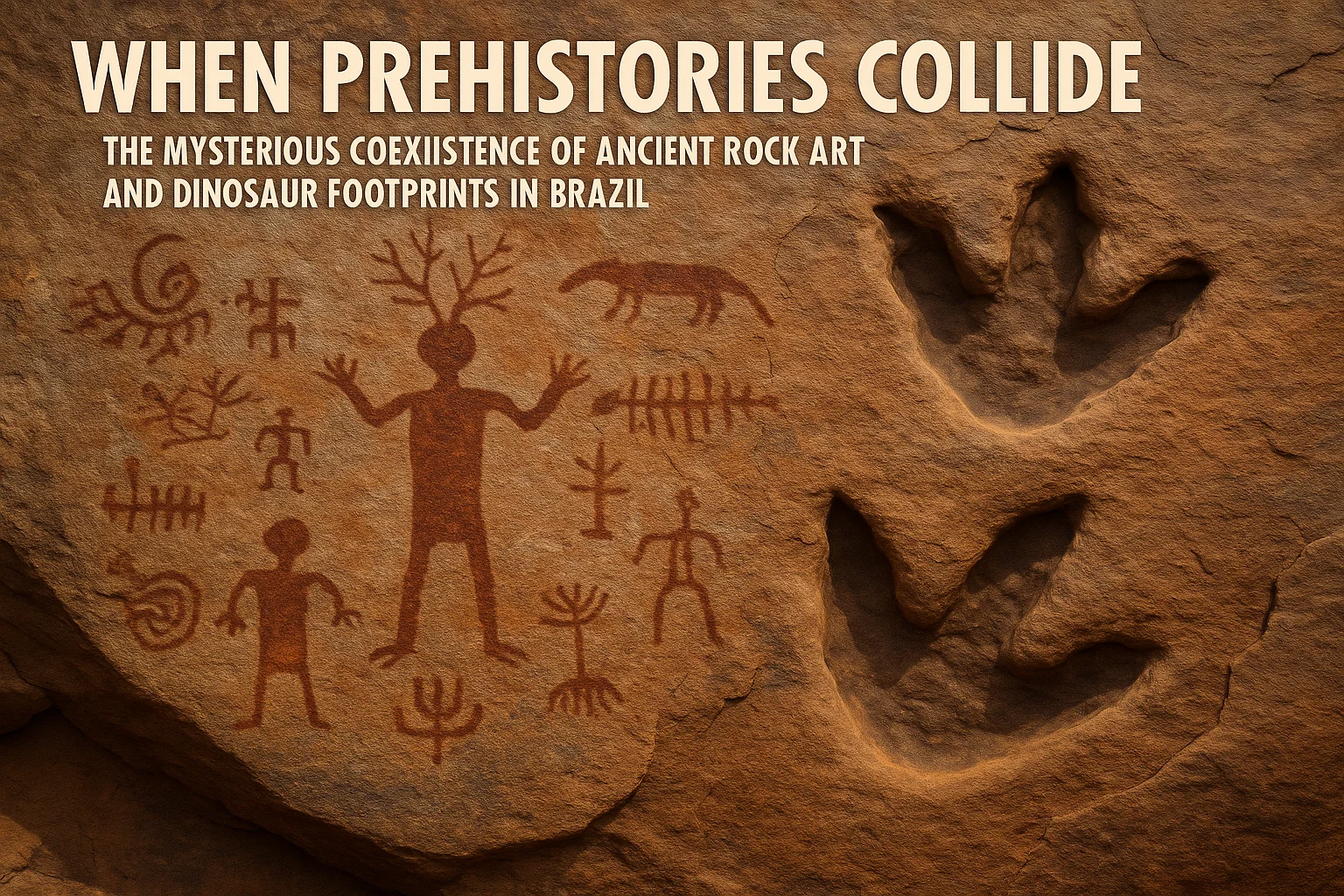

Ancient Rock Art and Dinosaur Footprints: Imagine standing on a vast slab of stone in the northeastern Brazilian sertão, the dry, sun-baked backlands. The air shimmers with heat. Before you, etched into the rock underfoot, are the unmistakable, three-toed impressions of a colossal creature that walked the earth millions of years ago. You are standing in the footprints of a dinosaur. Now, raise your eyes. On the vertical rock face beside you, painted in vibrant shades of red and ochre, are intricate geometric patterns, stylized human figures, and scenes of ritual and hunt, created by human artists thousands of years ago. This is not a scene from a fantasy novel; it is a real and profound reality at numerous archaeological sites across Brazil. Here, two distinct chapters of Earth’s history—the Age of Reptiles and the dawn of human culture—exist side-by-side, creating a powerful and enigmatic landscape that challenges our perception of time and narrative.

This unique convergence offers an unparalleled opportunity for scientists and visitors alike. It’s a place where paleontology, the study of ancient life, directly meets archaeology, the study of ancient human activity. The sites, most notably in the states of Paraíba and Piauí, form a dual heritage of immense value. They tell a story not of a single past, but of multiple pasts, separated by vast gulfs of time, yet now forever linked in the same stone canvas. This article will journey into the heart of these remarkable locations, exploring the science behind the dinosaur footprints, the cultural significance of the ancient rock art, and the fascinating, often puzzling, questions that arise from their shared existence. We will delve into the minds of the paleontologists who decipher the steps of titans and the archaeologists who seek to understand the symbolic world of Brazil’s earliest human inhabitants.

The Canvas of Stone: Understanding the Geological Stage

To comprehend how these two incredible records came to be preserved together, we must first understand the geology that made it all possible. The story begins around 140 to 110 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous period. At that time, the interior of what is now northeastern Brazil looked utterly different. It was a vast lowland environment, crisscrossed by braided river systems and dotted with extensive shallow lakes and mudflats—an ideal habitat for a diverse array of dinosaurs and other prehistoric life.

The ground these creatures walked upon was soft, saturated sediment, much like the mud on the banks of a modern river. When a dinosaur stepped down, its immense weight compressed the layers below, creating a mold of its foot. Subsequent layers of sediment gently filled these impressions, and over millions of years, these sediments hardened into solid rock—sandstone and siltstone. The former mudflat became a layer of rock, and the infilled prints became natural casts, preserving the precise details of the dinosaur’s foot in negative relief. This process created the perfect template for preservation. Eons later, the forces of tectonics and erosion lifted these layers and began to wear them away, exhumining the ancient footprints and exposing them on the surface for the first time since the Cretaceous.

This same geological canvas, now hardened into vast, flat rock exposures known as “lajidos” or “lajeiros” in Portuguese, later became the preferred drawing board for human populations. The smooth, light-colored, and often vertical surfaces of these same sandstone formations provided an ideal, durable surface for painting and engraving. The rock’s porosity may have even helped bind the mineral-based pigments used by the artists. Thus, the same geological processes that fossilized the dinosaur tracks also prepared the perfect, enduring surface for human artistic expression, setting the stage for an unintended collaboration across deep time.

Giants of the Cretaceous: Deciphering the Dinosaur Footprints

The dinosaur footprints found in Brazil, particularly in the Vale dos Dinossauros (Valley of the Dinosaurs) in Sousa, Paraíba, and the Serrote do Letreiro site in Paraíba, are among the most significant in the world. They are not isolated finds but rather extensive trackways—sequences of steps that allow paleontologists to reconstruct the behavior of these long-extinct animals with astonishing detail. Each print is a data point, a frozen moment in time.

By analyzing the shape, size, and depth of a footprint, scientists can identify the type of dinosaur that made it. Theropods, the carnivorous bipeds like the famous Tyrannosaurus rex (though earlier and often smaller in this region), typically left narrow, tridactyl (three-toed) prints with sharp claw marks. Sauropods, the colossal long-necked herbivores like Brachiosaurus, left enormous, elephant-like round prints from their hind feet and smaller, crescent-shaped prints from their front feet. Ornithopods, other herbivores like Iguanodon, left three-toed prints that are often broader and more rounded than those of theropods. Beyond identification, the trackways tell dynamic stories. The stride length indicates the animal’s speed and gait—was it walking, trotting, or running? The direction of multiple trackways can suggest herd behavior in sauropods or potential predatory scenarios if a theropod’s trackway intersects with that of a herbivore.

The concentration of footprints in these areas suggests they were thriving ecosystems. The data gleaned from these Brazilian trackways has been crucial in painting a picture of a vibrant Cretaceous world. They provide evidence that cannot be found from bones alone, offering a direct glimpse into the daily lives of these giants—their size, their social structures, and their interactions with the environment. They are the literal footsteps of history, a testament to a world ruled by reptiles.

The Human Artists: Masters of Symbol and Story

Millions of years after the last dinosaur fell, a new intelligent species arrived on the scene: Homo sapiens. The first human groups to reach northeastern Brazil, ancestors of the indigenous peoples of the region, found a landscape already rich with strange and powerful markings. We can only imagine what they thought of the massive, three-toed prints embedded in the rock. Did they recognize them as the tracks of immense animals? Did they incorporate them into their cosmology and myths?

What we do know is that they chose these very same rock formations as the primary location for their own profound artistic expressions. The ancient rock art of Brazil, particularly in the Serra da Capivara National Park area (though the phenomenon extends to the footprint sites), is some of the most sophisticated and abundant in the Americas. Created over a span of thousands of years, these paintings were not mere decoration; they were a fundamental part of human culture. Using pigments derived from iron oxides (reds and yellows), manganese (blacks), and kaolin (whites), mixed with animal fat or plant resins, these artists created a complex visual language.

The motifs are diverse and fascinating. They include:

- Geometric Designs: intricate patterns of lines, dots, zigzags, and spirals, whose precise meanings are often lost to time but likely held ritual or symbolic significance.

- Human Figures: often shown in dynamic poses, hunting, dancing, or engaging in communal activities. Some are adorned with headdresses and elaborate attire, suggesting rituals or denoting status.

- Animals: representations of the fauna that shared their world—deer, jaguars, armadillos, rheas, and many others, often captured with remarkable observational skill.

- Complex Scenes: perhaps the most compelling panels depict narratives, such as a great hunt, a honey-gathering expedition, or a communal dance, offering a priceless window into the daily and spiritual lives of these ancient communities.

This art served multiple purposes: it was a way to record knowledge and history, a means of transmitting culture to future generations, a component of shamanistic rituals, and a way to mark territory and identity. It was, in essence, their written language and their sacred text, painted onto the stone of their world.

The Teradactyl: Unmasking the Legend of the Prehistoric Sky

A Meeting Across Millennia: Intentional Co-Location or Coincidence?

The most captivating question surrounding sites that feature both ancient rock art and dinosaur footprints is the nature of their relationship. Did humans intentionally create their art next to these mysterious prints? If so, what did they believe them to be? The evidence suggests that the connection was far from coincidental.

At key sites like Serrote do Letreiro in Paraíba, the positioning of the petroglyphs (rock carvings) is strikingly deliberate in relation to the fossil footprints. The geometric designs are frequently carved in close proximity to, and sometimes even directly surrounding, the dinosaur tracks. This precise placement strongly implies that the human artists not only noticed the prints but were actively engaging with them. They were incorporating these natural features into their symbolic worldview.

Scholars propose several theories for this behavior. The most compelling is that the footprints held a deep spiritual or mythological significance for these cultures. Without the scientific framework of paleontology, they would have sought to explain the origins of these giant, bird-like impressions through their own belief systems. The prints might have been seen as the tracks of ancestral beings, powerful mythological creatures, or spirits from a creation story. By carving their symbols around them, they might have been attempting to harness the power of these entities, mark the site as sacred, or create a narrative that connected their community to the land and its mysterious past. It represents a form of paleo-artistic interpretation—an ancient attempt to make sense of fossilized evidence.

“The proximity of the petroglyphs to the footprints suggests that the human artists recognized the tracks as something significant, perhaps integrating them into their cosmogony. It’s a powerful intersection of deep time and human time.” — Dr. Luciano Carvalho, Brazilian Archaeologist.

This interaction transforms these sites from merely coincidental overlaps into truly integrated landscapes of meaning. They are not just two separate histories lying on the same rock; they are a single, complex palimpsest where one history actively interpreted and responded to the other.

Conservation at the Crossroads: Protecting a Dual Heritage

The incredible value of these sites is matched by their profound vulnerability. The same exposure that makes the footprints and art visible also subjects them to relentless forces of destruction. The threats are both natural and human-made, and the battle to preserve this heritage is constant and critical.

Natural threats include relentless weathering from sun, wind, and rain. Thermal expansion and contraction can cause the rock surface to crack and flake. Biological growth like lichens and algae can invade the rock art, breaking down the pigments and the stone itself. In more dramatic cases, erosion from water runoff or plant roots can obliterate entire sections of trackways or panels.

Human-made threats are often even more devastating. Vandalism, both intentional and unintentional, is a major concern. People walking on the footprints to take photographs erode the delicate details. Graffiti and scratching directly damage irreplaceable art. Furthermore, industrial expansion, including quarrying, mining, and the construction of infrastructure, poses a massive risk to entire sites. Looting of archaeological material and a simple lack of public awareness and funding for preservation efforts compound these problems.

Protecting these areas requires a multi-faceted approach. Fencing, controlled access, and the presence of trained guides help minimize direct human impact. Scientific monitoring using photogrammetry and 3D scanning creates high-resolution digital records of the sites, both for study and as a backup in case of damage. Perhaps most importantly, community engagement and education programs are vital. When local populations understand the global significance of the heritage in their backyard, they become its most passionate and effective guardians. Designations as national parks or UNESCO World Heritage Sites, like Serra da Capivara, provide crucial legal protection and resources for this ongoing work.

The Scientific and Cultural Impact of This Convergence

The significance of sites featuring both ancient rock art and dinosaur footprints extends far beyond their initial “wow” factor. They represent a unique nexus of scientific disciplines that offers richer insights than either record could provide alone. For paleontologists, the human context adds a fascinating layer to the fossil record. It provides a case study in how humans have interacted with and interpreted fossil evidence throughout history, long before the formal establishment of paleontology as a science.

For archaeologists and anthropologists, the dinosaur tracks become a key to understanding the cognitive and symbolic world of the ancient artists. The way these cultures chose to engage with the fossils reveals how they perceived their environment, how they constructed myths to explain the unknown, and how they integrated natural wonders into their spiritual practices. It provides a rare glimpse into the thought processes of pre-literate societies.

Culturally, these sites are invaluable. For the indigenous peoples of Brazil, they are a tangible link to their deepest ancestors, a testament to a cultural and artistic tradition that stretches back millennia. They are a source of identity and pride. For the nation of Brazil, they are a heritage of global importance, showcasing the country’s profound role in both the deep history of the planet and the story of human migration and artistic achievement in the Americas. For all of humanity, they are a powerful reminder of our place in deep time. They collapse millions of years into a single viewpoint, forcing us to contemplate the vast cycles of life, extinction, and emergence that have shaped our world, and the uniquely human drive to create, symbolize, and find meaning in the world around us.

Visiting the Sites: A Guide for the Modern Explorer

For those inspired to witness this convergence of histories firsthand, a trip to northeastern Brazil offers an unforgettable experience. Two primary areas stand out for their accessibility and stunning displays of both ancient rock art and dinosaur footprints.

Vale dos Dinossauros (Valley of the Dinosaurs), Sousa, Paraíba: This is the premier destination for dinosaur trackways in Brazil. A designated monument, it features over 20 distinct trackways with hundreds of footprints, primarily from theropods and sauropods. Well-maintained boardwalks allow visitors to view the prints without damaging them. While the rock art here is less prominent than the footprints, the area provides the essential context of the Cretaceous environment.

Serrote do Letreiro, Sousa, Paraíba: Located near the Vale dos Dinossauros, this is arguably the most important site for observing the direct interaction between the two records. Here, visitors can clearly see the intricate geometric petroglyphs carved by ancient humans encircling and surrounding the large theropod dinosaur footprints. It is the quintessential site to ponder the intentional connection between the two eras.

Serra da Capivara National Park, Piauí: A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this park is world-renowned for its density and quality of prehistoric rock art, with over 300 archaeological sites containing thousands of paintings. While dinosaur footprints are not the main focus here as they are in Paraíba, the park’s immense archaeological importance provides the crucial context for understanding the human side of this story—the culture and artistry of the people who might have encountered such fossils elsewhere.

| Site Name | Location | Primary Feature | Secondary Feature | Key Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vale dos Dinossauros | Sousa, Paraíba | Extensive dinosaur trackways | Geological context | One of the largest collections of dinosaur footprints in South America. |

| Serrote do Letreiro | Sousa, Paraíba | Direct overlap of petroglyphs & footprints | Dinosaur tracks | The clearest example of intentional human interaction with fossils. |

| Serra da Capivara | Piauí | Vast collection of ancient rock art | Archaeological sites | UNESCO site showcasing the pinnacle of prehistoric human artistry in the Americas. |

Tips for Responsible Visitation:

- Always use a guided tour. This supports the local economy and ensures you don’t accidentally damage fragile sites.

- Stay on designated paths and boardwalks. Never walk directly on the rock surfaces containing footprints or art.

- Look, but don’t touch. The oils from your skin can degrade both rock art and fossils.

- Take only photographs, leave only footprints. The preservation of these sites depends on everyone leaving them exactly as they were found.

Conclusion

The mysterious coexistence of ancient rock art and dinosaur footprints in Brazil is one of the world’s most fascinating archaeological and paleontological phenomena. It is a powerful testament to the layered nature of our planet’s history, where two entirely different epochs are superimposed onto a single, enduring stone canvas. These sites tell a dual narrative: one of mighty reptiles that once dominated the planet, their lives recorded only in the stone impressions of their footsteps, and another of intelligent, creative humans who arrived much later and sought to understand their world through magnificent art and symbol.

This convergence is more than just a curiosity; it is a profound reminder of our human impulse to find meaning in the natural world. The ancient artists of Brazil, standing before the same mysterious prints we study today with scientific rigor, asked the same fundamental questions we do: What is this? How did it get here? What does it mean? Their answers, etched in rock art surrounding the footprints, were spiritual and mythological. Our answers are scientific and empirical. Yet both are acts of interpretation, a dialogue with deep time. These sacred sites challenge us to bridge the gap between science and culture, between the empirical and the symbolic, and to appreciate the full, rich, and interconnected story of life on Earth. They remind us that history is not a single line, but a complex tapestry, and in the lajidos of Brazil, two of its most vibrant threads are woven inseparably together.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How old are the dinosaur footprints compared to the ancient rock art in Brazil?

The dinosaur footprints are vastly older. They date back to the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 110 to 120 million years ago. The ancient rock art, in contrast, was created by human beings relatively recently in geological terms. The earliest human arrival in South America is generally accepted to be within the last 20,000 to 15,000 years, with the rock art in these regions being created over the last several thousand years. This means there is a gap of over one hundred million years between the making of the footprints and the creation of the art.

Did the ancient humans who created the rock art know the footprints were from dinosaurs?

No, they did not know the footprints were from dinosaurs in the scientific sense. The concept of dinosaurs and their place in deep time was only established in the 19th century. However, the evidence strongly suggests that these ancient humans were keenly aware of the footprints. They recognized them as unusual and significant features of the landscape. They likely interpreted them through their own cultural and spiritual frameworks, perhaps seeing them as the tracks of giant mythological beasts, ancestral spirits, or creatures from their creation stories. The intentional placement of their art around the prints shows they were integrating them into their worldview.

Where is the best place to see both dinosaur footprints and ancient rock art together?

The most prominent and studied site for seeing both elements in direct proximity is Serrote do Letreiro in the state of Paraíba. It is located near the town of Sousa, which is also home to the larger Vale dos Dinossauros (Valley of the Dinosaurs). At Serrote do Letreiro, visitors can clearly see geometric petroglyphs (carved rock art) positioned directly alongside and encircling well-preserved theropod dinosaur footprints, making the intentional connection undeniable.

What is being done to protect these sensitive sites from damage?

Protection efforts are multi-layered. Many of the key areas are designated as protected cultural or natural monuments, which provides legal defense against industrial development. On the ground, physical protections like fencing, boardwalks, and controlled access points prevent visitors from walking on the fragile surfaces. Scientific teams use non-invasive techniques like 3D scanning to digitally preserve the sites. Crucially, education and community engagement programs are ongoing to raise awareness among both locals and tourists about the immense value and fragility of this heritage, turning the public into active stewards for its preservation.

Why is Brazil such a rich area for both dinosaur fossils and ancient rock art?

Brazil, particularly the northeastern interior, possesses a unique combination of geological and climatic conditions that led to this richness. The arid sertão region was once a lush Cretaceous ecosystem with ideal conditions (mudflats, lakes) for preserving dinosaur footprints. The same sedimentary rocks that captured these tracks were later exposed by erosion to form vast, smooth canvases perfect for rock art. Furthermore, the relatively stable climate and the protective overhangs of the rock formations helped shield both the footprints and the paintings from the worst weathering, allowing them to survive for millions and thousands of years, respectively.