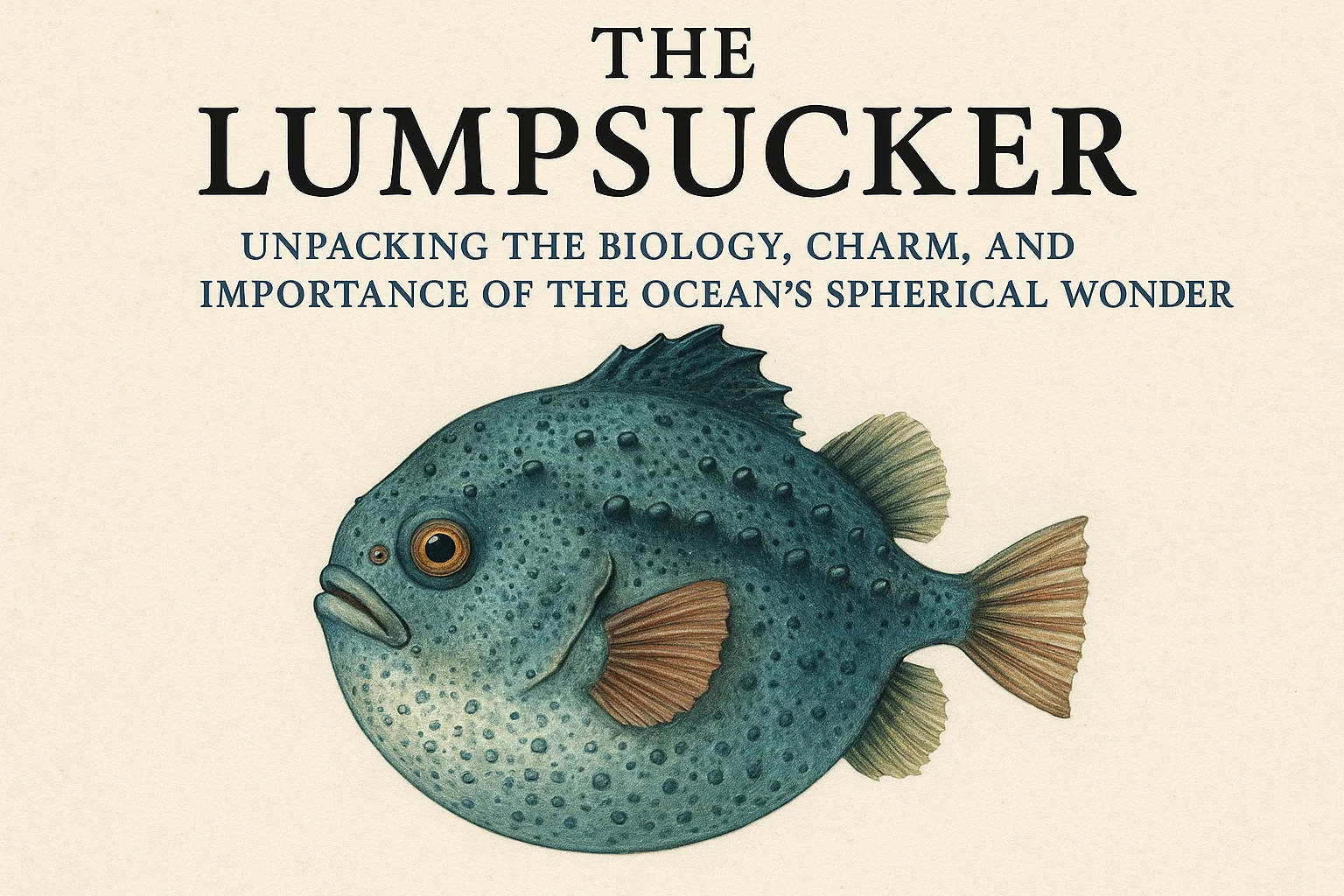

Imagine a fish that looks less like a streamlined predator and more like a perfectly round, grumpy ping-pong ball with fins. A creature that seems to defy the very laws of underwater hydrodynamics, opting for a spherical form that wobbles through the currents. This is not a character from a Pixar movie; this is the very real, utterly fascinating lumpsucker. Found in the cold, coastal waters of the Northern Hemisphere, these peculiar fish are a treasure trove of biological innovation and unexpected ecological importance. From their incredible suction disc to their crucial role in sustainable salmon farming, the humble lumpsucker is a testament to the fact that in evolution, sometimes the most unconventional design is the most brilliant. This article will take you on a deep dive into the world of these captivating fish, exploring everything from their unique anatomy and life cycle to their growing significance in modern aquaculture and the conservation efforts aimed at protecting them.

What Exactly Is a Lumpsucker?

Let’s start with the basics. The term “lumpsucker” doesn’t refer to a single species but to an entire family of fish known as Cyclopteridae. The name itself is a perfect descriptor: “lump” refers to their rounded, often bumpy bodies, and “sucker” points to their most defining feature—a modified pelvic fin that has evolved into a powerful, adhesive disc on their underside. This disc acts like a natural suction cup, allowing them to anchor themselves firmly to rocks, seaweed, and other surfaces in often turbulent waters. This adaptation is a masterclass in energy conservation; instead of constantly swimming against strong currents, a lumpsucker simply latches on and waits for the world to calm down.

The most common and widely recognized member of this family is the lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus). This species is the star of most photographs and is the one primarily involved in commercial aquaculture. However, the family includes other intriguing members like the spiny lumpsucker (Eumicrotremus orbis), a smaller, even more spherical species often found in the Pacific. Despite their differences, all lumpsuckers share that characteristic rotund body, a lack of a traditional swim bladder (which makes their buoyancy a constant challenge), and of course, that incredible ventral suction disc. They are a beautiful example of convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits to adapt to similar environments—in this case, a life clinging to surfaces in cold, rough seas.

The Anatomy of an Adorable Oddball

The lumpsucker’s body is a case study in functional, if bizarre, design. An adult lumpfish can grow up to two feet long and weigh over 20 pounds, though most are considerably smaller. Their bodies are almost perfectly spherical, covered not in typical scales but in a thick, gelatinous skin and a series of bony tubercles or bumps that form unique patterns. These tubercles, often described as being arranged in rows, provide a modicum of protection against predators. Their fins are another oddity. They possess a dorsal fin that is split into two parts: a spiny front section that is often hidden beneath the skin and a softer, rayed rear section. Their pectoral fins are large and fan-like, acting as the primary means of propulsion for their ungainly form.

But the true pièce de résistance of lumpsucker anatomy is the suction disc. Located on the belly between the pelvic fins, this disc is a highly specialized organ. It is surrounded by a fleshy fringe and is covered in tiny, fibrous structures that create immense suction when pressed against a smooth surface. The mechanism is so effective that prying a stuck lumpsucker off a rock or the glass of an aquarium requires significant force. This disc is not just for adults; it develops very early in a lumpsucker’s life. Once a larval lumpsucker undergoes metamorphosis, one of its first tasks is to find a suitable surface and practice latching on. This ability is crucial for their survival, allowing them to rest, avoid predators, and conserve energy in their dynamic aquatic world.

The Incredible Life Cycle of the Lumpsucker

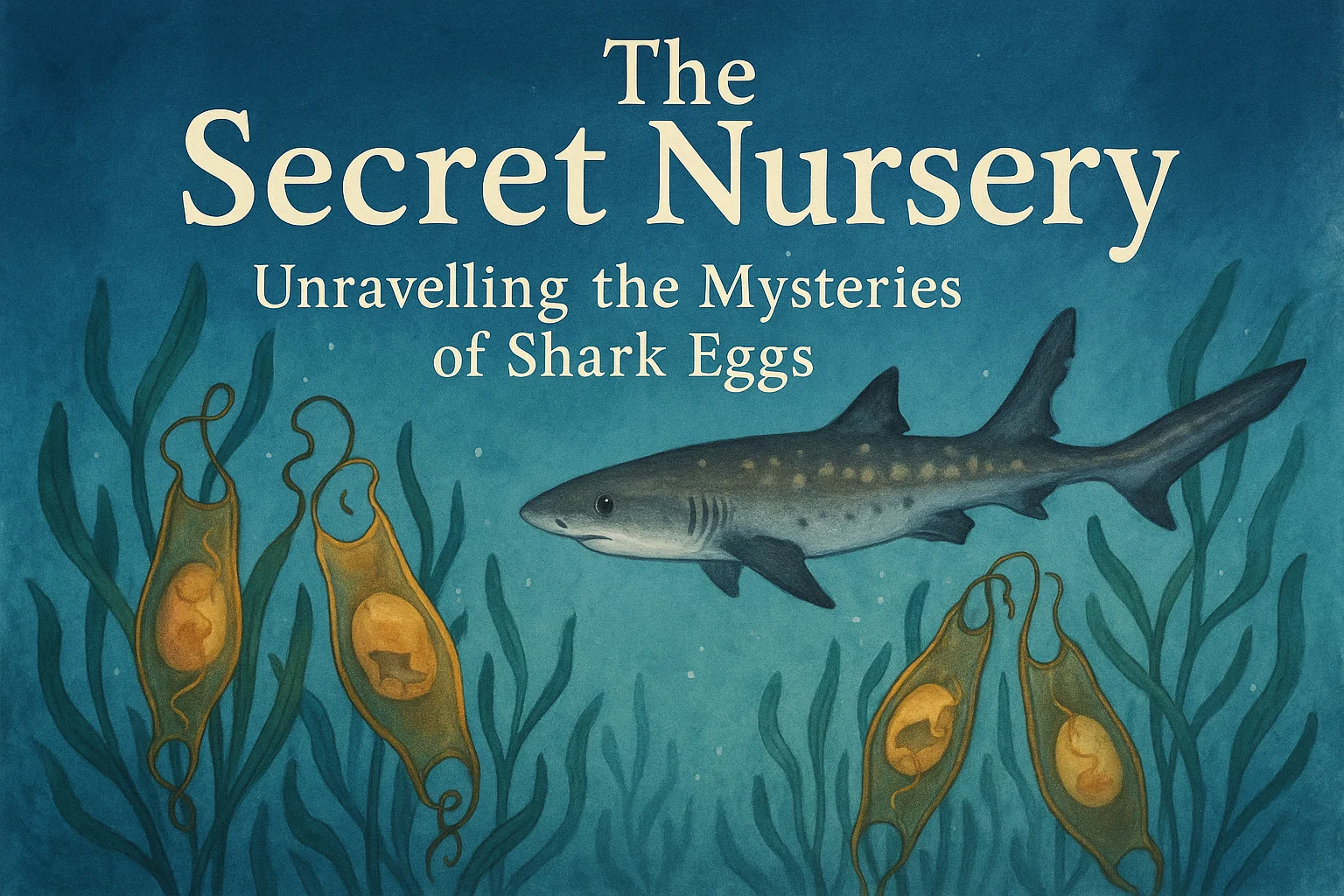

The life of a lumpsucker is a story of dramatic transformation and determined effort. It begins with spawning, which occurs in shallow waters during the spring. Female lumpfish are significantly larger than males and are responsible for producing vast quantities of eggs—a single large female can lay over 100,000 eggs in a mass. She deposits these sticky, often brightly colored (pink, red, or yellow) eggs into a rocky nest, which the male has prepared and will fiercely guard. This is where the male’s role becomes paramount. He becomes a dedicated father, fanning the eggs with his fins to provide oxygenated water and aggressively defending them from any would-be predators until they hatch.

After hatching, the larval lumpsuckers are initially free-swimming and look nothing like their spherical parents. They are tiny, transparent, and possess a more conventional fish-like shape. This pelagic phase allows them to disperse with ocean currents. After several weeks, they undergo a remarkable metamorphosis. Their body begins to shorten and swell into the characteristic round shape, their suction disc develops, and their bony tubercles start to form. Once this transformation is complete, the young lumpsuckers descend from the open water to a benthic (bottom-dwelling) lifestyle. They use their new suction disc to cling to seaweed and rocks in shallower waters, where they will spend their juvenile years growing and maturing before eventually moving to deeper offshore waters as adults.

Masters of Camouflage and Survival

While their suction disc is their primary defense, lumpsuckers are not entirely helpless when detached. Their first line of defense is often their color and texture. Their lumpy, often algae-encrusted bodies provide excellent camouflage against rocky substrates. They can also change their color to some degree to better match their surroundings, shifting from greens and grays to more muted browns. This ability to blend in makes them incredibly difficult for predators like seals, larger fish, and even seabirds to spot when they are holding still and latched onto a surface.

If camouflage fails and they are dislodged, their second line of defense is their surprising resilience. Their gelatinous skin and lack of a rigid internal structure make them a difficult and somewhat unappetizing mouthful for many predators. Furthermore, their spherical shape is deceptively robust. When threatened, some species can inflate themselves with water, making themselves even harder to swallow. While they are slow, clumsy swimmers, their large pectoral fins can generate quick bursts of movement to dart to a new hiding spot. It’s a survival strategy built not on speed or strength, but on stickiness, stealth, and being an generally unpalatable, rubbery ball.

Lumpsuckers and Humans: From Bycatch to Aquaculture Star

For centuries, lumpsuckers were primarily known to fishermen as bycatch—an oddity occasionally hauled up in nets. However, their eggs have a long history in some Nordic countries. Lumpfish roe, often dyed a vibrant red or black and marketed as a more affordable alternative to sturgeon caviar, has been a traditional garnish and delicacy. The harvesting of wild lumpsuckers for their roe became a small-scale industry, but it was the boom in salmon aquaculture that catapulted this peculiar fish into commercial prominence.

The salmon farming industry faces a significant challenge: sea lice. These parasitic crustaceans attach to farmed salmon, causing health problems, stunted growth, and massive economic losses. While chemical treatments exist, they are costly, can harm the environment, and lice are developing resistance. The solution? Biological control. And this is where the lumpsucker found its calling. These fish are voracious and natural cleaners, eagerly feeding on the sea lice that plague salmon. They are peaceful, coexist well in net pens with salmon, and don’t compete for the salmon’s feed. This discovery turned the lumpsucker from an obscure curiosity into a highly sought-after “cleaner fish.”

“The use of lumpsuckers as cleaner fish is one of the most successful examples of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. It’s a natural solution to a complex problem.” — Dr. Eva Johansson, Marine Biologist

The demand for lumpfish in salmon farms, particularly in Norway, Iceland, and Scotland, has skyrocketed. This has led to the development of a massive aquaculture industry dedicated solely to breeding and raising lumpfish. hatcheries now produce millions of juvenile lumpfish every year to be deployed as sea lice patrol in salmon pens. This symbiotic relationship has significantly reduced the reliance on chemical pesticides and has made salmon farming more sustainable and environmentally friendly.

Conservation Status and Environmental Concerns

The rapid rise of the lumpsucker aquaculture industry is not without its own set of challenges and ethical considerations. The large-scale collection of wild broodstock (mature fish used for breeding) has raised concerns about the impact on natural populations. While the lumpfish is currently listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List due to its wide distribution, localized depletion is a real possibility if not managed carefully. Sustainable aquaculture practices now emphasize breeding from captive stocks to alleviate pressure on wild fish.

Furthermore, the welfare of the lumpfish themselves within salmon farms is a growing area of research. Are the conditions in the pens suitable for their specific needs? Factors like water temperature (lumpsuckers prefer colder water), the availability of suitable surfaces for attachment, and their overall health and mortality rates are being closely studied. The goal is to ensure that this symbiotic relationship is truly mutually beneficial and that the welfare of the cleaner fish is prioritized. Research into optimizing hatchery conditions, improving diets, and ensuring better survival rates in sea cages is ongoing and critical for the long-term ethics and sustainability of this practice.

Listao Tuna: The Unsung Hero of the Ocean and Your Pantry

The Cultural Impact of the Spherical Fish

Beyond their biological and economic roles, lumpsuckers have carved out a unique niche in human culture, primarily due to their undeniable and internet-friendly cuteness. Their round bodies, large eyes, and seemingly perpetual frown have made them a social media sensation. Photographs and videos of lumpsuckers, especially the tiny, colorful spiny lumpsuckers, regularly go viral, charming millions with their awkward swimming and tenacious clinging.

This popularity has translated into a minor commercial boom. Lumpsuckers have become mascots for marine conservation, featured on everything from plush toys and keychains to enamel pins and T-shirts. They appear in comic strips and animated shorts, almost always portrayed as the grumpy but lovable underdog of the ocean. This cultural embrace has had a positive side effect: raising public awareness about a previously obscure family of fish. People who fall in love with a funny picture of a lumpsucker are often inspired to learn more about marine biology, conservation, and the complexities of our ocean ecosystems.

The Future of Lumpsucker Research

The scientific community’s interest in lumpsuckers extends far beyond their cleaning services. Their unique biology presents a plethora of fascinating research avenues. Materials scientists are intensely interested in the biomechanics of their suction disc. Understanding the morphology and physics behind this natural adhesive could lead to breakthroughs in the design of man-made suction cups that work effectively on rough and wet surfaces—a longstanding engineering challenge. Potential applications range from improved medical devices to underwater robotics and industrial manipulators.

Geneticists are also sequencing the lumpsucker genome to better understand the genes responsible for their unique development, including the formation of their tubercles and their incredible metamorphosis from a larval form to a spherical adult. Furthermore, physiologists study how they manage osmoregulation (water and salt balance) and buoyancy without a swim bladder. Each peculiarity of the lumpsucker offers a potential key to unlocking a new scientific or technological innovation, proving that this oddball fish is a treasure trove of biological inspiration.

How to See a Lumpsucker in Person

For those captivated by these spherical wonders and eager to see one up close, there are a few reliable options. Many large public aquariums, particularly those with cold-water marine exhibits, now feature lumpsuckers in their collections. Their unusual appearance and behavior make them a popular display animal. The Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, the Alaska SeaLife Center, and numerous aquariums throughout Scandinavia and the UK often have lumpfish or spiny lumpsuckers on display. Watching them navigate their tank, latching onto the glass and then pushing off with their pectoral fins, is a delightful experience.

For the more adventurous, encountering a lumpsucker in the wild is possible but requires specific knowledge and conditions. Snorkeling or diving in cold, rocky, coastal environments with abundant kelp forests during the spring and summer months offers the best chance. They are masters of camouflage, so a keen eye is necessary to spot them clinging to a blade of kelp or tucked against a rock. Remember, they are wild animals and should be observed without disturbance. Their suction power is immense, so trying to handle one would likely stress the animal and could potentially injure it.

A Quick Guide to Lumpsucker Species

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Typical Size | Key Distinguishing Feature | Primary Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumpfish | Cyclopterus lumpus | Up to 60 cm (24 in) | Large size, pronounced bony tubercles in rows | North Atlantic Ocean |

| Spiny Lumpsucker | Eumicrotremus orbis | Up to 12.5 cm (5 in) | Very spherical, covered in spiny tubercles | North Pacific Ocean |

| Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker | Eumicrotremus orbis | Up to 5 cm (2 in) | Tiny, bright colors (green, orange), perfect sphere | Northern Pacific coasts |

| Atlantic Spiny Lumpsucker | Eumicrotremus spinosus | Up to 7 cm (2.8 in) | Similar to Pacific but in Atlantic | North Atlantic coasts |

Conclusion

The lumpsucker is a magnificent contradiction. It is a fish that seems to defy the very essence of what a fish should be—streamlined and graceful. Instead, it is a comical, rotund, sticky creature that wobbles through life. Yet, within that unconventional form lies a stunning example of evolutionary adaptation. Its suction disc is a biological marvel, its life cycle a story of dedication and transformation, and its role in the ecosystem, both natural and man-made, is increasingly vital. From being a mere curiosity to becoming an unsung hero of sustainable aquaculture and a muse for scientists and artists alike, the lumpsucker teaches us an important lesson: value often comes in the most unexpected packages. By understanding, appreciating, and protecting these spherical wonders of the deep, we not only safeguard a unique species but also embrace the boundless creativity and interconnectedness of life on our planet.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How strong is a lumpsucker’s suction disc?

A lumpsucker’s suction disc is incredibly powerful relative to its size. The disc creates a vacuum seal that can withstand strong currents and waves. It requires significant force to pry a determined lumpsucker off a smooth surface like glass or rock. This strength is crucial for their survival, allowing them to conserve energy and avoid being swept away or eaten.

Are lumpsuckers good pets?

While they are adorable, lumpsuckers are not suitable pets for home aquarists. They are cold-water marine fish that -specialized, chilled aquarium systems to maintain the low temperatures they need to thrive. They can also be sensitive to water quality and have specific dietary needs. Their unique lifestyle, requiring clean surfaces to attach to, also makes their care complex and best left to professional aquarists in public aquariums.

What do lumpsuckers eat?

Lumpsuckers are opportunistic carnivores. In the wild, their diet consists mainly of small crustaceans like copepods, amphipods, and worms. Larger individuals may also eat jellyfish and small fish. In their role as cleaner fish in salmon farms, they are prized for their appetite for sea lice, which they pluck directly from the skin of the salmon.

Why are they called ‘lumpsuckers’?

The name is a direct description of the fish’s most prominent features. “Lump” refers to their rounded, often bumpy (with tubercles) body shape. “Sucker” refers to their highly modified pelvic fins that have fused together to form a powerful suction cup on their underside, which they use to attach to surfaces.

Is lumpfish caviar sustainable?

The sustainability of lumpfish roe depends on how the fish are sourced. Traditionally, roe was harvested from wild-caught fish, which raised concerns about population impacts. However, with the rise of lumpsucker aquaculture for the cleaner fish industry, a significant portion of lumpfish roe now comes as a byproduct from farmed fish that are harvested after their cleaning service in salmon pens is complete. This integrated approach is generally considered a more sustainable model for producing the caviar.