Imagine gliding through the warm, sun-dappled waters of the sea when a shadow, longer than a school bus, slowly emerges from the blue. Instead of fear, a sense of awe washes over you. This isn’t a predator from the deep; it’s a gentle, spotted behemoth, gliding with an almost otherworldly grace. This is the tiburon ballena, the whale shark. Despite its imposing name and staggering size, this filter-feeding giant is one of the ocean’s most docile and enigmatic residents. It’s a creature of superlatives: the largest fish in the world, a global traveler, and a living canvas of stars. In this deep dive, we’ll explore everything that makes the tiburon ballena a true wonder of the marine world, from its unique biology and global habitat to the conservation efforts dedicated to ensuring its future.

The name “tiburon ballena” itself is a fascinating starting point. In Spanish, “tiburón” means shark and “ballena” means whale. This perfectly encapsulates the paradox of this animal. It has the cartilaginous skeleton and morphology of a shark, but it reaches the colossal size of some whales and, like many large whales, it feeds on some of the ocean’s smallest organisms. This gentle nature is a stark contrast to the fearsome reputation of its predatory cousins. For decades, the life of the tiburon ballena was shrouded in mystery. Only recently, with advances in satellite tagging and genetic testing, have scientists begun to unravel the secrets of their long migrations, their reproductive habits, and their social behaviors. Each discovery adds another layer of fascination to this already incredible animal, highlighting its critical role in marine ecosystems and the urgent need to protect it.

What Exactly is a Tiburón Ballena?

Let’s clear up the most common misconception right away: the tiburon ballena is a shark, not a whale. It belongs to the order Orectolobiformes, the carpet sharks, which might seem surprising given that most of its relatives are bottom-dwellers like the wobbegong. The whale shark is the sole member of the family Rhincodontidae and the genus Rhincodon typus. Its classification as a shark means it’s a fish—a very, very big fish. It breathes through gills and has a cartilaginous skeleton, which is lighter and more flexible than bone, a necessity for an animal of its immense proportions.

So, what earns it the “whale” moniker? The answer is twofold: size and feeding strategy. A fully grown tiburon ballena can reach lengths of up to 18 meters (60 feet) or more, though most observed today are between 5.5 and 10 meters long. This places them firmly in the size range of large whales. More importantly, they are filter feeders. They do not hunt large prey with rows of sharp teeth. Instead, they swim through the water with their enormous mouths wide open, passively filtering vast quantities of plankton, krill, small fish, and sometimes even small squid or crustaceans. This method of feeding, called “ram filtration,” is remarkably similar to that of baleen whales, which use baleen plates instead of teeth to sieve their food from the water. This convergent evolution—where two unrelated species develop similar traits to adapt to similar ecological niches—is the reason behind its common name.

The Anatomy of a Giant

Every aspect of the tiburon ballena‘s physiology is engineered for a life of efficient, large-scale filter feeding. Its body is robust and streamlined, tapering to a powerful, distinctively dual-lobed caudal fin (tail) that can propel it at a cruising speed of around 5 km/h (3 mph). Its most striking feature is its head—broad and flattened, with a terminal mouth that can stretch up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) wide. Inside that mouth are about 300 rows of tiny teeth, but these play almost no role in feeding. They are a vestigial reminder of its evolutionary past.

The real filtration system is in the gills. As the shark swims forward, water flows into its mouth and out through its five massive gill slits on each side. Just before the water exits, it passes through a unique spongy, mesh-like tissue called the branchial sieve. This structure acts like a net, trapping any particles larger than 2-3 millimeters. The shark periodically closes its mouth and swallows the collected mass of food. To enhance this efficiency, the tiburon ballena can also engage in “coughing,” a behavior where it sharply expels water backward through its gills to clear the sieve of any debris that might clog it.

Perhaps the most captivating anatomical feature is its skin. The tiburon ballena is adorned with a breathtaking pattern of light spots and stripes against a dark gray, blue, or brown background. This pattern is not just for show; it serves as a unique identifier. Much like a human fingerprint, the spot pattern behind the gills and above the pectoral fin is distinct to each individual, allowing scientists and citizen scientists to identify and track specific sharks through photo-identification databases. This pattern may also play a role in camouflage, breaking up the shark’s outline when viewed from below against the shimmering surface light.

A Global Citizen: Where to Find the Whale Shark

The tiburon ballena is a truly cosmopolitan species, found in all tropical and warm-temperate seas around the globe. They prefer surface water temperatures between 21°C and 30°C (70°F – 86°F) and are highly migratory, following seasonal blooms of plankton and spawning events of fish and corals. Their movements are complex and still not fully understood, but they are known to aggregate in specific locations at predictable times of the year, often driven by an abundance of food.

Some of the world’s most famous gathering spots for tiburon ballena include the coast of Quintana Roo in Mexico, particularly around Isla Holbox and Isla Mujeres, where they congregate in the summer to feast on the eggs of the little tunny fish. In Belize, the Gladden Spit is renowned for gatherings that coincide with the spawning of snapper. In Southeast Asia, the waters off Cenderawasih Bay in Indonesia and Donsol in the Philippines are famous hotspots. The Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia hosts a massive annual aggregation between March and July, which has become a model for sustainable ecotourism. Other key locations include the Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, the Maldives, and the Galapagos Islands.

“The whale shark is a powerful symbol of the health of our oceans. Where they thrive, it indicates a rich and functioning ecosystem.” — Dr. Brad Norman, Marine Scientist and Founder of ECOCEAN.

These aggregations can be spectacular, sometimes featuring dozens of individuals feeding peacefully together. However, it’s important to note that their presence is not guaranteed. Their migratory patterns are influenced by oceanographic conditions like currents, upwellings, and water temperature, which themselves are being affected by climate change. This makes their movement patterns a key area of scientific study.

The Secret Life and Mysterious Reproduction of the Tiburón Ballena

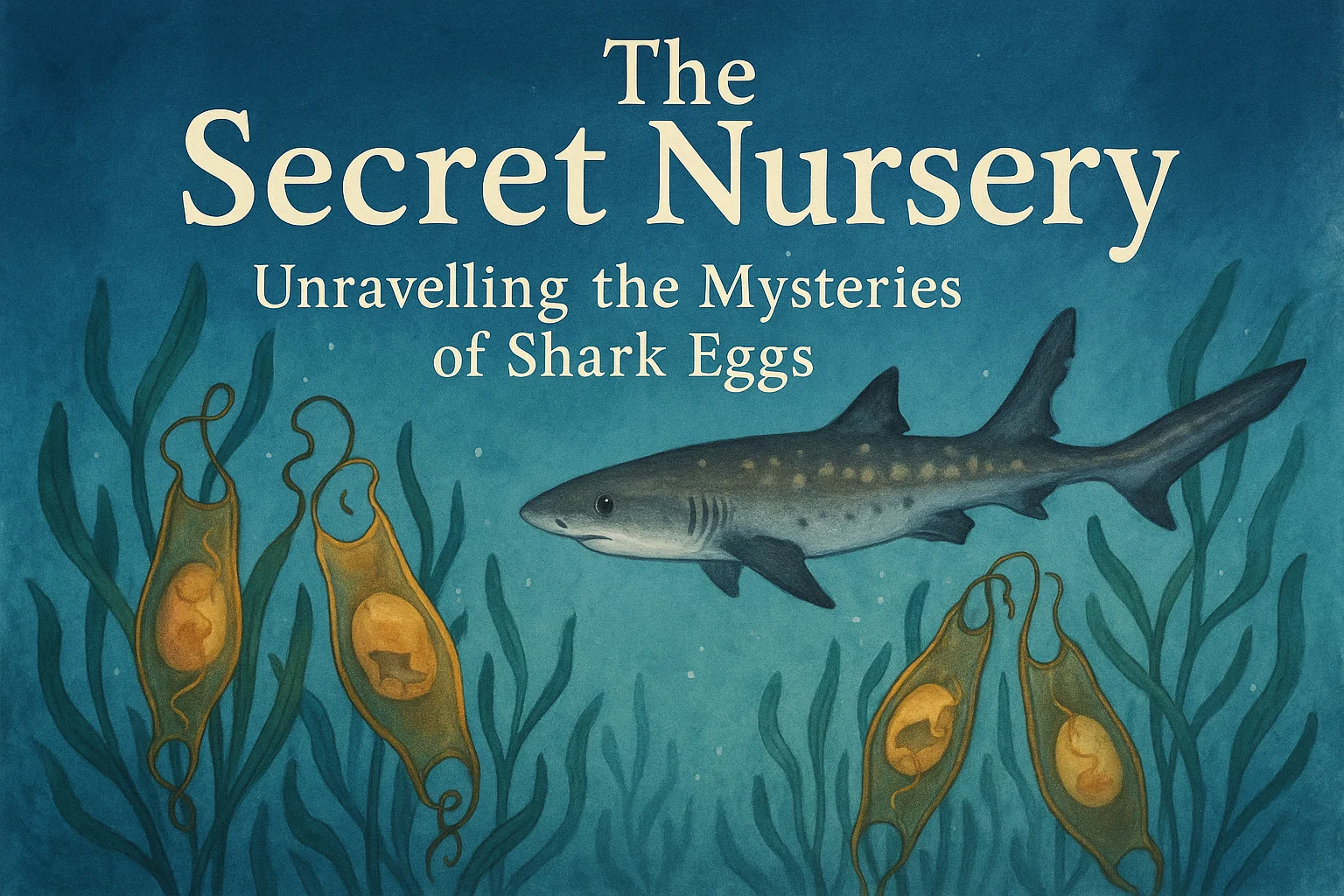

For a creature so large, the tiburon ballena has managed to keep much of its life history, especially its reproductive habits, a profound secret. They are believed to be slow-growing and very long-lived, with some estimates suggesting a lifespan of 70 to 100 years, perhaps even longer. They also take a long time to reach sexual maturity, potentially not until they are around 30 years old. This late maturity is a critical factor in their population dynamics and makes them highly vulnerable to threats, as it takes a long time to replace individuals that are lost.

The reproduction of the tiburon ballena was a complete mystery until a monumental discovery in 1995. A female shark was harpooned off the coast of Taiwan and was found to be pregnant with a staggering 304 pups. This single finding revealed that whale sharks are ovoviviparous. This means the eggs develop and hatch inside the female’s body, and she gives birth to live, fully-formed young. The pups found in Taiwan ranged in size from 42 to 64 cm (16.5 to 25 inches) long. This reproductive strategy of producing a huge number of offspring is likely an evolutionary adaptation to ensure that at least a few survive the perilous early stages of life in the open ocean, where they are vulnerable to predators.

Despite this groundbreaking discovery, a pregnant female has never been documented since. No one has ever observed mating, and the pupping grounds remain one of oceanography’s great unsolved mysteries. Scientists are using satellite tags and genetic analysis to try to locate these critical areas, as protecting them is essential for the species’ long-term survival. Each new piece of data brings us closer to understanding the complete life cycle of this magnificent animal.

Following the Food: The Diet of a Filter Feeder

The menu for a tiburon ballena is written in the smallest print imaginable. As an obligate filter feeder, its survival depends on the availability of dense patches of microscopic prey. Its primary food source is zooplankton, which includes tiny animals like copepods, krill, and fish larvae. However, they are also known to opportunistically feed on larger aggregations of food, such as small squid, sardines, anchovies, and even the spawn of larger fish.

Their feeding strategy is not always passive. While “ram feeding” is their default mode, they have also been observed actively sucking in water in a more targeted way or even hanging vertically in the water column, sucking prey down from the surface—a behavior known as “vertical feeding.” They are also known to associate with other marine life; for example, they will often follow schools of tuna that drive smaller fish to the surface, or they will wait near groups of diving birds, which are also a sign of a concentrated food source below.

The relationship between the tiburon ballena and its prey is a delicate dance driven by ocean productivity. They follow ocean currents that concentrate plankton, and they are often found in areas where deep, nutrient-rich water upwells to the surface, fueling massive blooms of the organisms they depend on. This makes them important indicators of ocean health. Their presence signals a productive, thriving ecosystem. Conversely, their absence or decline can be a warning sign of broader oceanic imbalances.

The Human Connection: From Mythology to Ecotourism

Humanity’s relationship with the tiburon ballena has evolved dramatically over centuries. In many coastal cultures, encounters with these leviathans spawned legends and myths. In Vietnam, the whale shark is revered and called “Ca Ong,” which translates roughly to “Sir Fish,” and is considered a deity that brings good luck and protection to fishermen. In the Philippines, some communities believed they could absorb the sickness of a person by swimming near them.

For much of the 20th century, however, the primary interaction was through targeted fisheries. They were hunted for their meat, fins, and oil. The liver oil was used to waterproof boats, and the fins command a high price in the shark fin trade. This hunting, particularly in key areas like Taiwan and India, led to significant population declines.

Today, the paradigm has shifted in many parts of the world. A living tiburon ballena is now recognized as being infinitely more valuable than a dead one. Whale shark ecotourism has become a multi-million dollar global industry. People from all over the world travel to destinations like Mexico, Australia, and the Philippines for the chance to snorkel alongside these majestic creatures. This economic incentive has become a powerful conservation tool, encouraging local communities and governments to protect the sharks and their habitats.

However, this tourism must be managed responsibly. Poorly conducted tours can stress the animals, disrupt their feeding, and lead to injuries from boat propellers. The success of tiburon ballena ecotourism depends on strict guidelines, such as limiting the number of boats and people, maintaining a safe distance, and prohibiting touching or flash photography.

The Looming Shadows: Threats Facing the Gentle Giant

Despite its size, the tiburon ballena is vulnerable to a host of anthropogenic threats. In 2016, its status on the IUCN Red List was escalated from Vulnerable to Endangered, a clear indicator that its global population is in decline.

- Bycatch: Perhaps the most significant threat is accidental capture in fishing gear. As they feed near the surface, they can become entangled in gillnets, purse seines, and longlines set for other species like tuna. This bycatch is often fatal.

- Vessel Strikes: Their surface-feeding behavior and large size make them highly susceptible to collisions with large ships. These strikes can cause catastrophic injuries and are a major source of mortality, particularly in busy shipping lanes.

- Habitat Degradation and Pollution: Pollution from coastal development, agricultural runoff, and plastics degrades their marine habitat. Microplastics are a particular concern, as they are ingested during filter feeding and can accumulate in the shark’s digestive system, potentially causing toxicity or blocking nutrient absorption.

- Climate Change: The effects of a warming climate are multifaceted. It can alter ocean currents that concentrate plankton, disrupt the timing of spawning events that the sharks rely on, and cause ocean acidification, which can affect the base of the food web. Changes in sea temperature may also force the sharks to alter their migratory routes.

- Illegal Fishing: Targeted illegal fishing for their fins, meat, and oil continues in some areas, driven by high demand in certain markets.

The combination of these threats is particularly dangerous for a species that is slow to reproduce. Losing even a few mature adults can have a devastating impact on the overall population.

Listao Tuna: The Unsung Hero of the Ocean and Your Pantry

Guardians of the Giant: Conservation Efforts and How You Can Help

The precarious situation of the tiburon ballena has sparked a global movement to protect it. Conservation efforts are underway on international, national, and local levels. The species is listed on Appendix II of CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), which regulates and monitors international trade in its products. It is also covered by the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), encouraging range states to cooperate on its protection.

Many countries have implemented strict national protections. India, the Maldives, the Philippines, and Mexico, among others, have banned all fishing for whale sharks within their waters. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have been established in key aggregation zones, such as the Gladden Spit in Belize and the Ningaloo Reef in Australia, to safeguard critical habitat.

Scientific research is the backbone of effective conservation. Organizations like ECOCEAN run a global photo-identification library that allows anyone to upload photos of a whale shark’s spot pattern. This citizen science approach has helped researchers track individual sharks across oceans and over decades, providing invaluable data on their life span, growth rate, and migration routes. Satellite tagging programs are also crucial, revealing previously unknown migratory pathways and helping to identify areas that need protection.

| Conservation Action | How It Helps the Tiburón Ballena |

|---|---|

| International Agreements (CITES, CMS) | Regulates trade and promotes cross-border cooperation on protection strategies. |

| National Fishing Bans | Prohibits the targeted hunting of whale sharks within a country’s Exclusive Economic Zone. |

| Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) | Safeguards critical feeding and aggregation sites from human disturbance and fishing. |

| Photo-ID Databases (e.g., ECOCEAN) | Engages the public in research and provides data on population size, movements, and life history. |

| Satellite Tagging | Maps migration routes, identifies threats like shipping lanes, and locates potential pupping grounds. |

| Responsible Ecotourism Guidelines | Ensures that tourism provides economic benefits without harming the sharks or their behavior. |

As an individual, you can contribute to the survival of the tiburon ballena in several meaningful ways:

- Choose Responsible Ecotourism: If you go on a whale shark tour, research the operator thoroughly. Choose one that follows strict guidelines, keeps a respectful distance, and educates its guests.

- Support Conservation Organizations: Donate to or volunteer with groups dedicated to shark research and conservation, such as ECOCEAN, WWF, or MarAlliance.

- Be a Conscious Seafood Consumer: Choose seafood that is sustainably caught to help reduce bycatch. Look for certifications like MSC (Marine Stewardship Council).

- Reduce Your Plastic Footprint: Minimize your use of single-use plastics to help keep our oceans clean and safe from microplastic pollution.

- Report Sightings: If you are lucky enough to see a tiburon ballena in the wild, you can upload your photos to the ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-Identification library to contribute to citizen science.

Conclusion

The tiburon ballena is more than just the world’s largest fish; it is a testament to the grandeur, mystery, and fragility of life in our oceans. This gentle giant, with its starlit skin and peaceful demeanor, captivates all who are fortunate enough to encounter it. From the mysteries of its deep-water births to its epic transoceanic journeys, it reminds us how much we have yet to learn about the blue heart of our planet. However, its endangered status is a stark warning. The threats of bycatch, ship strikes, and pollution are symptoms of a larger human impact on the marine environment. The story of the tiburon ballena is still being written. Through dedicated global conservation efforts, responsible tourism, and individual actions, we can ensure that this majestic species continues to glide through the world’s oceans for generations to come, a living constellation inspiring awe and driving our commitment to protect the wonders of the deep.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How big can a tiburon ballena actually get?

Historical reports and estimates have suggested maximum sizes of up to 18-20 meters (60-65 feet), but these are difficult to verify. The largest reliably measured individuals are typically in the range of 12 to 14 meters (40-46 feet). The average size of most whale sharks seen today is between 5.5 and 10 meters (18-33 feet). Females are generally larger than males. Their immense size is a key reason why they are such an effective filter feeder, allowing them to process enormous volumes of water.

Is it safe to swim with a tiburon ballena?

Yes, it is generally considered very safe to swim with a tiburon ballena. They are docile, filter-feeding animals with no interest in humans as prey. They do not have large, predatory teeth designed for biting. However, safety also depends on human behavior. It’s crucial to follow the guidelines provided by ethical tour operators: maintain a respectful distance (often 3-4 meters), do not touch the shark, and never block its path. Their large tails, while not aggressive, can unintentionally deliver a powerful swipe if a person gets too close.

Why is the pattern on a tiburon ballena’s skin so unique?

The beautiful pattern of light spots and stripes on a dark background is the whale shark’s unique fingerprint. No two patterns are exactly alike. This allows researchers to use photographic identification to track individuals over time and across vast distances, building a database that helps estimate population sizes, understand growth rates, and map migratory routes. The pattern may also serve as a form of camouflage, known as countershading, helping to break up the shark’s outline when viewed from below.

What is the biggest threat to the survival of the tiburon ballena?

It’s difficult to pinpoint a single biggest threat, as they face a combination of serious challenges. However, bycatch—being accidentally caught in fishing gear intended for other species like tuna—is likely the leading cause of mortality globally. Their surface-feeding behavior makes them extremely vulnerable to entanglement in nets. Additionally, ship strikes in busy shipping lanes and the ongoing effects of climate change on their food sources and habitat are major, escalating threats to their populations.

How many tiburon ballena are left in the world?

It is impossible to know the exact global population of whale sharks. They are wide-ranging, spend a lot of time deep underwater, and are difficult to count. However, all available evidence points to a population that has been declining for decades. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that the global population may have been reduced by more than 50% over the last 75 years, which is why they are classified as Endangered. Ongoing research using photo-ID and tagging is helping scientists get a better, though still incomplete, picture of their numbers and trends.