You see a picture of a magnificent, large-eared elephant. Is it from the savannas of Africa or the forests of Asia? For many, telling the difference between an Asian elephant and an African elephant is a classic trivia question, but the distinctions run far deeper than just a single physical feature. These two magnificent creatures, while both belonging to the elephant family, have evolved separately for millions of years, leading to a fascinating array of differences in their anatomy, behavior, and social structures.

Understanding the “asian elephant vs african elephant” debate is not just about satisfying curiosity; it’s about appreciating the unique adaptations of two of the planet’s most intelligent and ecologically vital species. This comprehensive guide will take you on a journey into the world of these gentle giants, equipping you to identify them with confidence and deepening your understanding of their incredible lives.

Getting the Big Picture: An Overview of Two Species

Before we dive into the specific details, it’s crucial to understand that we’re not just comparing two types of the same elephant. The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and the African elephant (Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis) are entirely different genera, meaning their genetic separation is significant. Think of it as the difference between a tiger (Panthera) and a lion (Panthera)—they’re related but distinct species. The most common African elephant is the bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), while the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) is now recognized as a separate species, though it shares many of the broader African traits we’ll discuss.

The evolutionary paths of these elephants diverged on different continents, leading them to adapt to vastly different environments. African elephants roamed the open savannas, dense forests, and sprawling deserts of a massive continent, while Asian elephants evolved in the tropical rainforests, grasslands, and mountainous regions of Asia. This geographical separation is the root cause of all the physical and behavioral differences we observe today. It’s a classic story of evolution shaping life to fit its surroundings perfectly.

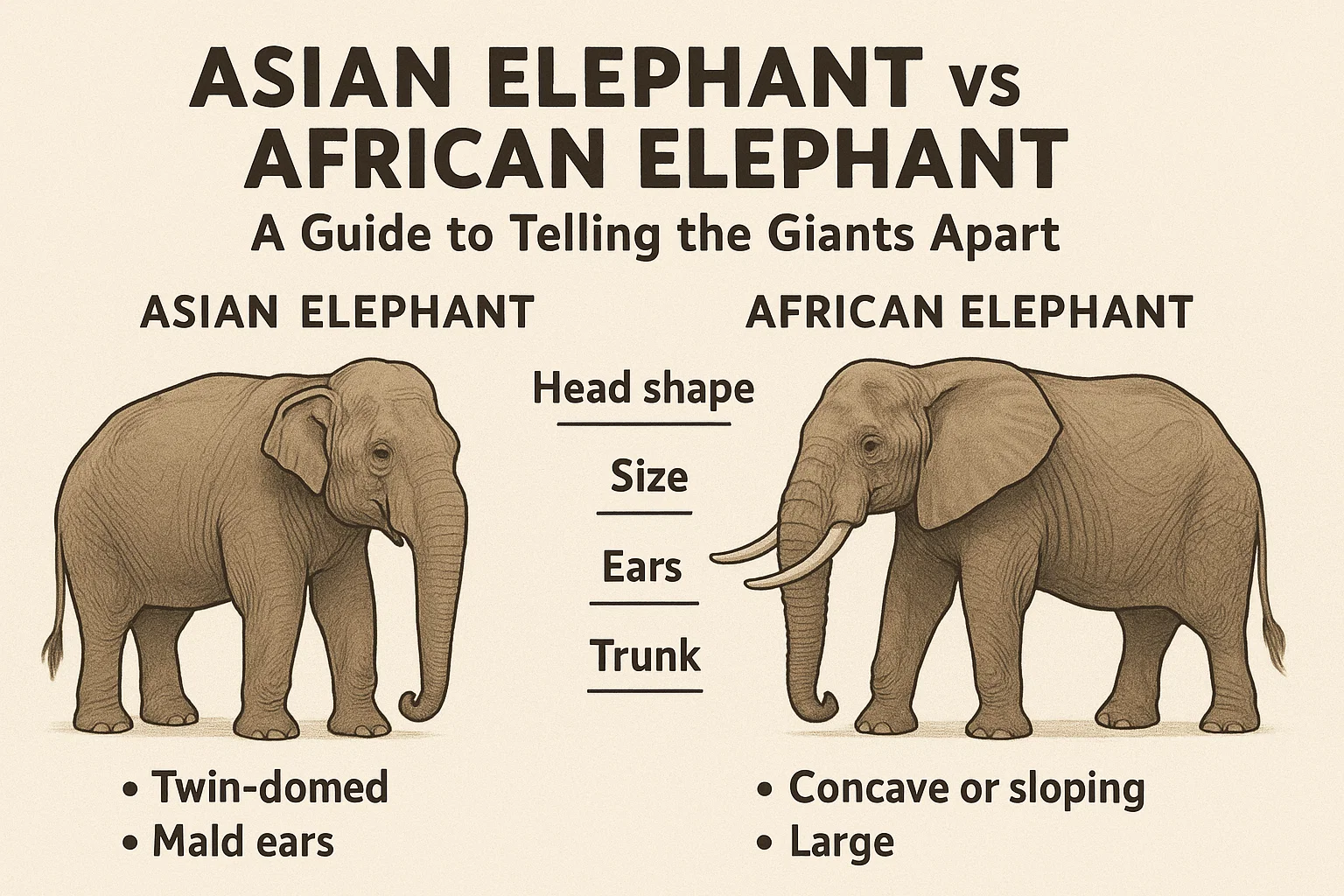

The Head and Skull: A Tale of Two Profiles

One of the most immediate ways to distinguish between these two giants is by looking at the shape of their head and the structure of their skull. The forehead of an Asian elephant is characterized by two prominent domes, or twin-domed head, with a noticeable indent running right down the center. This gives them a somewhat rugged, bumpy appearance. In contrast, the African elephant has a single, sloping dome that curves smoothly from the top of its head down to the base of its trunk. Their forehead is much rounder and less angular.

The overall skull shape further highlights their differences. An Asian elephant’s skull is proportionally lighter and shorter, while the African elephant’s skull is heavier, longer, and more robust. This difference in cranial structure is not just for show; it relates to muscle attachment points for their trunks and tusks, and potentially even to their dietary needs. The domes on an Asian elephant’s head are filled with sinuses, making the skull lighter—a potential advantage for moving through dense forest undergrowth where a heavier head might be a hindrance.

The Ears: Nature’s Air Conditioners

Perhaps the most famous differentiator in the “asian elephant vs african elephant” comparison is the size and shape of their ears. It’s a classic identifier: large ears mean African, and smaller ears mean Asian. But why such a dramatic difference? The answer lies in climate and thermoregulation. African elephants inhabit a generally hotter, sun-baked environment. Their enormous ears, often described as being shaped like the continent of Africa itself, act as massive radiators. They are filled with a complex network of blood vessels.

By flapping these large ears, African elephants create a cooling breeze and circulate blood close to the surface, allowing them to release excess body heat into the air. It’s a highly effective natural air-conditioning system. Asian elephants, living in slightly more shaded and often forested environments that can be hot but also humid, don’t face the same extreme radiant heat. Consequently, their ears are smaller, more rounded, and proportioned closer to their head. They still use them for communication and swatting insects, but their role in cooling is not as critical as it is for their African cousins.

The Trunk: A Masterful Tool with a Tip-Top Difference

Both Asian and African elephants possess a trunk, a phenomenal multi-purpose tool that is a fusion of the nose and upper lip. It contains tens of thousands of muscles, allowing for incredible strength and delicate precision. However, the tips of these trunks are configured quite differently. The African elephant’s trunk tip is a spectacular instrument that features two distinct, finger-like projections at its end—one on the top and one on the bottom. This pincer-like grip gives them excellent dexterity for grasping objects, plucking leaves, and siphoning up water.

The Asian elephant’s trunk tip offers a fascinating contrast. It has a single, finger-like projection only on the top. The bottom of the tip is smooth and flat. To pick something up, an Asian elephant will often use its single “finger” to curl around an object and press it against this smooth lower lip, almost like a human thumb pressing against a finger. This difference in trunk-tip anatomy is a beautiful example of evolutionary adaptation to different foraging styles and food sources in their respective habitats.

Tusks and Teeth: Ivory and Dentition

The presence of tusks—which are actually elongated incisor teeth—is another area where the two species commonly differ, though with important exceptions. Generally speaking, among African elephants, both males and females routinely grow large, prominent tusks. These tusks are used for digging for water and minerals, stripping bark from trees, and as weapons in dominance fights. They are often curved and can grow to an immense size.

In Asian elephants, the story is different. Typically, only the males grow large, prominent tusks. Many male Asian elephants, called “makhnas,” are actually tuskless. Female Asian elephants may have very small tusks called “tushes,” which are barely visible or may not protrude from the mouth at all. This disparity is linked to genetics and evolutionary pressure. Furthermore, their molars (grinding teeth) have a different pattern. Asian elephant molars have compressed enamel loops, while African elephant molars have more of a diamond-shaped pattern. These dental differences are adaptations to their specific diets.

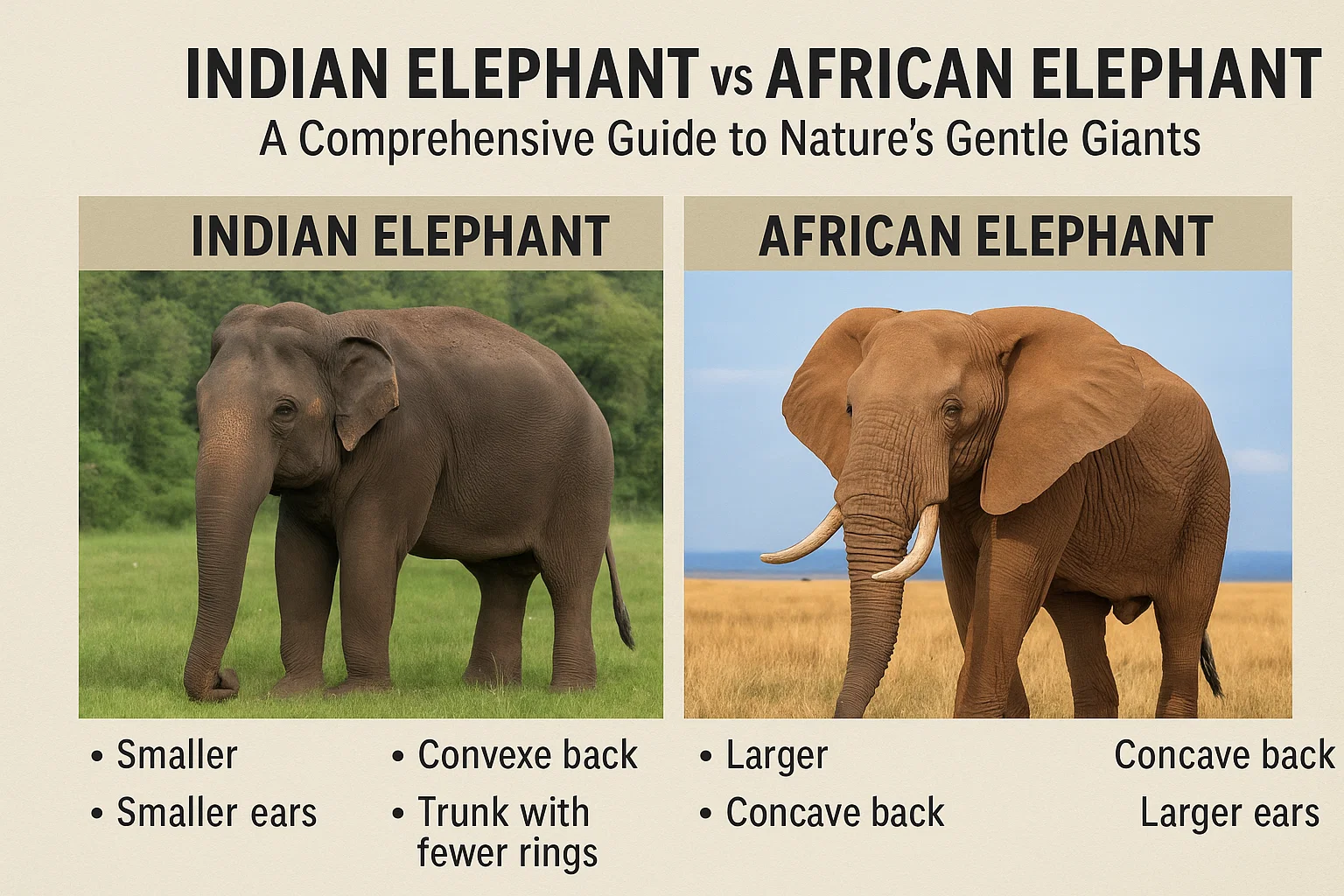

Body Size and Shape: Built for Different Worlds

The question of which elephant is bigger has a clear answer: the African elephant takes the prize. African bush elephants are the largest land animals on Earth. A large male African bush elephant can stand up to 13 feet tall at the shoulder and weigh an astonishing 6,000 to 7,000 kilograms. They have a distinct concave or swayed curve to their back, giving them a somewhat “sagging” appearance.

Asian elephants are generally smaller and stockier. A large bull Asian elephant might reach about 9 to 10 feet at the shoulder and weigh up to 5,000 kilograms. Their body shape is more level, with a straight back or sometimes even a convex curve, making the highest point of their body often the crown of their head. Their legs are also thicker and stockier in proportion to their body height compared to the longer, more pillar-like legs of the African elephant, which may be an adaptation for supporting their greater weight and for navigating different types of terrain.

Skin Texture: Wrinkles and More

At a glance, all elephants look wrinkly, but the texture of their skin has distinct characteristics. An African elephant’s skin is more heavily wrinkled and appears rougher. These deep crevices and cracks help to trap and retain moisture, which is a critical adaptation for surviving in hot, arid environments. As water or mud is applied to the skin, it gets caught in these wrinkles, slowing evaporation and keeping the elephant cooler for longer periods.

Asian elephant skin is not as dramatically wrinkled. It is smoother to the touch and covered in more hair, particularly on the head, back, and around the tail. Young Asian elephant calves can be surprisingly hairy, and while much of this hair is lost as they age, adults retain more coarse hair than African elephants. This difference is likely another thermoregulatory adaptation, with the hair potentially helping to wick away moisture in their more humid Asian habitats.

Habitat and Geographical Distribution

The names themselves give away their primary homes: Asian elephants are found in Asia, and African elephants are found in Africa. But the specific types of environments they inhabit within these continents are key to understanding their biology. African elephants have a vast range that spans sub-Saharan Africa. They are incredibly adaptable and can be found in a wide variety of ecosystems, including dense tropical forests (forest elephants), open savannas, grasslands, woodlands, and even deserts like the Namib.

Asian elephants have a more fragmented and limited distribution across South and Southeast Asia. Their populations are found in countries like India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia (Borneo and Sumatra), and China. They primarily inhabit tropical evergreen forests, dry deciduous forests, grasslands, and shrublands. Their range is much more constrained by human development and the availability of forested corridors.

Social Structure and Herd Dynamics

Both species are highly social and matriarchal, meaning herds are led by the oldest and most experienced female. However, there are subtle differences in their social organization. African elephant herds are often larger and can be quite complex, sometimes consisting of dozens of individuals from multiple related families. These larger groups can merge into temporary “clans” around water sources or particularly rich feeding grounds. The matriarch holds immense knowledge about migration routes and water holes.

Asian elephant social groups tend to be smaller and more cohesive, typically composed of closely related females and their offspring, averaging around 6 to 8 individuals. Bonds within these smaller herds are incredibly strong. Another key social difference involves males. In both species, male elephants leave their natal herd upon reaching puberty. However, African male elephants often lead more solitary lives or form loose, transient bachelor groups. Asian male elephants, particularly outside of the mating season (musth), are more likely to be solitary or sometimes associate in very small, less stable bachelor groups.

Diet and Foraging Behavior

All elephants are herbivores, but their specific diets and foraging techniques reflect their different habitats and physical adaptations. African elephants are primarily browsers and grazers. They use their immense size and strength to push over trees to access roots and branches, and their tusks to dig for water. They consume a huge variety of vegetation, including grasses, leaves, twigs, bark, fruit, and flowers. Their impact on the landscape can be so significant that they are considered “ecosystem engineers,” creating clearings that allow new plants to grow.

Asian elephants are also mixed feeders but tend to be more dedicated browsers in forest environments. Their diet consists mainly of grasses, bark, roots, leaves, and stems of a wide variety of plants and trees. They are particularly fond of crops like bananas, rice, and sugarcane, which brings them into frequent and dangerous conflict with humans. Their foraging style, aided by their single-point trunk tip, is often more precise, carefully plucking specific leaves and shoots.

Conservation Status: A Shared Struggle for Survival

Tragically, when comparing the “asian elephant vs african elephant,” their most profound commonality is that they are both facing severe threats to their survival. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, the Asian elephant is classified as Endangered. Their primary threats are habitat loss and fragmentation due to human expansion, agriculture, and infrastructure development. This leads to increased human-elephant conflict, where elephants raid crops and sometimes harm people, leading to retaliatory killings. Poaching for ivory, meat, and skin also remains a significant problem.

The African elephant faces an equally dire situation. The African savanna elephant is listed as Endangered, and the African forest elephant is listed as Critically Endangered. Their greatest threat in recent decades has been intense poaching for the international ivory trade. Habitat loss and human-elephant conflict are also major pressures. While both species are protected by international law, enforcement is challenging, and their populations continue to decline in many parts of their range. Conservation efforts for both are multifaceted, involving anti-poaching patrols, habitat protection and creation of corridors, community-based conservation programs, and human-elephant conflict mitigation strategies.

Cultural Significance and Human Relations

Both elephant species have been deeply intertwined with human cultures for millennia, but in strikingly different ways. In many Asian cultures, particularly in India, Thailand, and Sri Lanka, the Asian elephant is a revered figure. It is deeply embedded in religion and mythology, most famously associated with the Hindu god Ganesha, the remover of obstacles. For centuries, Asian elephants have been captured and trained for use in forestry, religious ceremonies, and tourism. This relationship is complex, encompassing both reverence and exploitation.

The historical relationship between humans and African elephants has been different. While they feature prominently in African folklore and art, they were not traditionally domesticated for labor. Their immense size, more volatile nature, and the fact that both sexes have tusks made them more dangerous and less suitable for domestication compared to the more manageable Asian elephants. The primary human interaction with African elephants, especially in the colonial and modern eras, has been through hunting and, more recently, wildlife tourism and photography safaris, which are a critical source of revenue for conservation.

The Role in the Ecosystem: Keystone Species

Whether in Asia or Africa, elephants play an irreplaceable role as keystone species and ecosystem engineers. Their daily activities profoundly shape the environments they live in. By pushing over trees and stripping bark, they help maintain savanna and grassland habitats, preventing forest encroachment. This creates habitats for countless other species that rely on open spaces. Their dung is crucial for seed dispersal; many plant species have seeds that must pass through an elephant’s digestive system before they can germinate.

Furthermore, their dung acts as a fertilizer and provides a microhabitat for insects and other invertebrates. The water holes they dig during the dry season become vital sources of water for other animals. The loss of elephants from an ecosystem causes a cascade of negative effects, leading to reduced biodiversity and fundamentally altered landscapes. Protecting elephants is not just about saving a single iconic species; it is about preserving the health and functionality of entire ecosystems.

Behavioral Differences and Intelligence

Both Asian and African elephants are renowned for their intelligence, self-awareness, and complex emotional lives. They have large, highly developed brains and exhibit behaviors such as tool use, problem-solving, mourning their dead, and vocal communication that includes infrasound—low-frequency sounds that travel over long distances. However, subtle behavioral differences exist, often shaped by their environments and social structures.

African elephants, living in more open environments with greater predator pressure (especially on calves from lions and hyenas), can sometimes display more overtly defensive and potentially aggressive behaviors when threatened. Their larger herd sizes may also necessitate more complex communication. Asian elephants, often navigating dense forests and a landscape heavily modified by humans, exhibit incredible problem-solving skills related to finding food and navigating human barriers. Their long history of co-existence and domestication has also shaped a unique interspecies relationship with humans, though this is not without its ethical concerns.

The Subtleties of Communication

Elephant communication is a rich tapestry of vocalizations, body language, touch, and seismic signals. Both species use a similar repertoire of sounds, from trumpets and rumbles to roars and cries. The deep rumbles that travel through the ground as vibrations are a key part of their long-distance communication. However, some research suggests there might be dialectical differences in the vocalizations between the species, much like regional accents in human language.

Body language is also crucial. Ear spreading is a classic threat display in African elephants, made more dramatic by their enormous ear size. Asian elephants may rely more on head movements and trunk postures in their displays. Touch, especially within the close-knit family herds of Asian elephants, is a constant form of bonding and reassurance, with trunks often intertwined. The subtle differences in their communication styles are a rich field of study for scientists seeking to understand the depths of elephant cognition and sociality.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The basic reproductive biology of both elephant species is similar, characterized by a long gestation period and extended calf care. Females of both species have a gestation period of nearly 22 months—the longest of any land mammal. They typically give birth to a single calf, which will nurse for several years and remain under the protection and tutelage of the mother and the entire herd for up to 16 years. This extended childhood is necessary for the calf to learn the complex social rules and survival knowledge it needs.

One notable difference is in the reproductive strategy of males. In both species, males experience periodic musth, a state of heightened aggression and sexual activity linked to a massive surge in reproductive hormones. However, this state can be more pronounced and longer-lasting in African elephant bulls. The intense competition for mates in African elephant society, where many males are potential rivals, may have driven this adaptation. The social dynamics around mating and musth are complex and vary between the species based on population density and sex ratios.

The Enigmatic World of the Black Monkey: More Than Meets the Eye

A Quick-Reference Comparison Table

| Feature | Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus) | African Elephant (Loxodonta africana) |

|---|---|---|

| Head Shape | Twin-domed, with a central indent | Single, rounded dome; sloping forehead |

| Ears | Smaller, rounded shape | Very large, shaped like the African continent |

| Back | Level or convex (arched) | Concave (dipped or swayed) |

| Skin Texture | Smoother with more hair | Heavily wrinkled, rough |

| Tusks | Usually only on males; females often lack them | On both males and females |

| Trunk Tip | Single “finger” at the top | Two “fingers,” one on top and one on bottom |

| Body Size | Smaller; up to 10 ft tall, 5,000 kg | Larger; up to 13 ft tall, 7,000 kg |

| Habitat | Tropical forests of Asia | Savannas and forests of Africa |

| IUCN Status | Endangered | Endangered (Savanna), Critically Endangered (Forest) |

In Their Own Words: Quotes on the Giants

“The question of whether an Asian elephant is more intelligent than an African elephant is like asking if a hammer is a better tool than a saw. They are both supremely intelligent, but their minds have been shaped by different environments to solve different problems.” — A noted wildlife biologist.

“Elephants are a keystone species. When you protect an African savanna or an Asian rainforest for elephants, you protect every single other species that shares that habitat. They are the architects of their worlds.” — A leading conservationist.

“The difference in their ears is the first thing you learn, but the difference in their soul, in the way an African matriarch leads her herd across the dusty plain versus how an Asian matriarch navigates a forest edge—that is something you feel.” — An experienced wildlife guide.

Conclusion

The journey of exploring the “asian elephant vs african elephant” reveals a story of magnificent divergence. From the sweeping savannas of Africa to the dense jungles of Asia, evolution has sculpted two uniquely adapted, intelligent, and awe-inspiring creatures. While their differences in ears, head shape, tusks, and size provide us with easy identifiers, the true distinction lies in the intricate details of their lives—their social nuances, their ecological roles, and their profound relationships with the human world.

Both species, however, stand on a precipice, facing unprecedented threats to their existence. Understanding and appreciating their differences is the first step toward fostering a deeper respect and a stronger commitment to ensuring that the rumble of both Asian and African elephants continues to resonate through their respective lands for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the single easiest way to tell an Asian elephant apart from an African elephant?

The single easiest way is to look at the ears. African elephants have enormous ears that are shaped like the continent of Africa itself. Asian elephants have significantly smaller, more rounded ears that seem proportionate to their head size. This feature is almost always visible and is a very reliable indicator, making it the go-to method for a quick identification in the “asian elephant vs african elephant” debate.

Can Asian and African elephants interbreed?

No, they cannot. Despite both being elephants, the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) belong to different genera. This genetic distance is too great for successful interbreeding. They have a different number of chromosomes, and even if artificial insemination were attempted, the biological barriers would prevent the creation of a hybrid. They are as reproductively isolated as, for example, a dog is from a bear.

Which elephant species is more aggressive?

It is a misconception to label one species as inherently more aggressive than the other. Both Asian and African elephants are generally peaceful and social animals. However, both can become extremely dangerous if provoked, threatened, or especially if protecting their young. African elephants, particularly bulls in musth or mothers with calves, can be highly defensive. Asian elephants, due to living in closer proximity to humans and experiencing more habitat pressure, are often involved in human-elephant conflict, which can be perceived as aggression. Temperament varies greatly by individual, experience, and context.

Where can I see both types of elephants?

You can see these magnificent animals in many major accredited zoos and wildlife sanctuaries around the world that participate in conservation breeding programs. To see them in their natural habitats, you would need to travel to their native continents. For Asian elephants, popular ecotourism destinations include national parks in Thailand, Sri Lanka, India (like Corbett or Kaziranga), and Nepal. For African elephants, the best places are on safari in countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, South Africa, and Namibia.

Are there different types of African elephants?

Yes, this is a critical point. There are two distinct species of African elephant: the African savanna (or bush) elephant (Loxodonta africana) and the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis). The forest elephant is slightly smaller, with darker, straighter, and downward-pointing tusks, and more rounded ears. They inhabit the dense rainforests of the Congo Basin. While they share the classic African elephant traits like large ears and two trunk fingers, they are genetically distinct and face even greater threats, being listed as Critically Endangered.